No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

On February 3rd and 4th, sophomores and juniors participated in the preliminary round of the 2020 Robert H. Lebow Oratorical Competition. While the student body had the opportunity to watch the six finalists in the all-school assembly, they did not have the chance to hear all of the contestants perform their speeches and listen to their stories. All of the messages presented by the participants are important to the community, and as a result, excerpts from a few first-round speeches have been provided.

Brian Li: “The Neglect of Humanities in the 21st Century”

The humanities serve as the foundation for human civilization. They teach us how to think critically and creatively. They facilitate empathy and compassion. We communicate more clearly, understand cultural values, and are introduced to new perspectives through the humanities. Humanistic education has been the core of liberal arts since the ancient Greeks, challenging students through art, literature, and politics. The humanities bring clarity to the future by reflecting on the past. Perhaps most importantly, they allow us to explore and understand what it means to be human. We need, now more than ever, to be able to understand the humanity of others. And while STEM is undoubtedly beneficial for humankind, we cannot sustain the neglect of the humanities for much longer without suffering severe consequences. With revolutionary technology like AI and genetic engineering, the humanities are essential to ensure that we progress ethically and morally together.

Andrew Wong: “Where do you see yourself in 10 years?”

A question many of us in this room have heard in countless interviews, and yet it is a question that can reveal so much about ourselves. So, where will we be in 10 years? In 10 years, we will have found ourselves going through the entire college process and graduating from Pingry. We will go to and then graduate from college. We will have the rest of our lives splayed out in front of us, ready to grasp in our hands, as we enter the real world, ready to be the next generation of business people, engineers, doctors, lawyers, politicians, world leaders, and so much more. That answer seems pretty easy and straightforward, right? In reality, not so much.

Lauren Drzala: “An Uphill Battle”

As time went by, I was falling behind on work because I could not write at all, leaving me frustrated in school. In addition, my mental health was at an all-time low. I began to isolate myself, believing that no one could really understand how I was feeling. It was like I was falling and no one was there to catch me. On top of that, I was told I could not play my sport this winter, nor could I play the piano, an instrument that I have been playing since I was nine. I felt out of control and just had to watch the train wreck happen. I thought my friends had moved on so I tried to as well, but I just felt stuck. Left behind. I was in this mind set for a while, but it wasn’t until I realized that I could not give up on myself and settle for this empty feeling that my life started getting back on track. This triggered an uphill battle to try and climb my way out of the dark.

Aneesh Karuppur: “Straying from the Tune”

We are always told that “small steps will lead you to your goal” and “you won’t even know how much effort it really takes if you do it one step at a time.” But people forget that for this advice to work, you have to actually be looking at your feet and making sure that every step is in the right direction. Otherwise, you simply aren’t going to notice until you’re too far away from your goal to make a correction.

By Justin Li (V)

In the last year-and-a-half, the departures of teachers such as Mr. Peterson, Ms. Taylor, and Mr. Thompson did not pass without controversy and speculation. Despite the uncertainty clouding most of these departures, it is undeniable that each one these teachers, and every faculty member at Pingry, offers something unique to the community; this year, the absences of these teachers have made us especially aware of this fact. As such, their departures left many of us feeling disappointed, and in many cases confused.

By speaking one-on-one with a few students, I have gleaned that the effect of these recent departures and the broader issue of teacher turnover is a topic students want to discuss. Aneesh Karuppur (V), for example, tells me that he is specifically “concerned regarding the number of departures each year, as it hurts the continuity throughout the years, as well as the solidity of Pingry’s teaching style and curriculum.” He also mentions that “as more and more of the Magistri faculty leave each year, it’s very important to secure replacements who will be able to stay at Pingry for similarly long periods of time.“

The foundation of an effective education, especially at Pingry, is the student-teacher relationship, and the concerns of Aneesh and many others raise important questions about Pingry as an educational institution. However, it is important to examine whether concerns like these are even justifiable. Looking past the particularly conspicuous departures in recent years, is teacher turnover really an issue at Pingry? Is the administration doing enough to make Pingry a place where teachers want to teach, and keep teaching?

To begin my investigation, I took a quantitative approach. In search of a reliable faculty database, I spoke with Dr. Dinkins, who informed me that such a resource was not readily accessible and instead advised me to look through past yearbooks. While yearbooks would not allow me to examine metrics, like average faculty tenure, using them in combination with departing faculty articles in the Record’s annual commencement issues allowed me to generate an annual proportion of departing faculty. This statistic would provide a broad picture of teacher turnover each year, which I could further categorize by department.

At home, I laid out the yearbooks I had accumulated on my bookshelf from 2012 to 2019 and recorded the number of Upper and Middle School faculty in each department each year, as well as the number of Magistri across all three campuses (I chose to exclude administrators since their turnover does not necessarily fit within the scope of my investigation and a large portion of administrators also taught classes in other departments). I added the department totals to obtain a total number of teaching faculty, making an effort to avoid double-counting faculty members who appeared in multiple departments, such as Mr. Lear or Ms. Thuzar.

I found that from 2012 to 2018, the proportion of faculty departures remained relatively consistent. The only notable feature of the graph occurs in 2019, where 9.4% of total teaching faculty departed and the graph indicates a significant upward spike, giving some justification to the recent concern. Nevertheless, I don’t believe that this singular spike, which could very likely be an outlier, indicates any overarching issue with teacher turnover at Pingry. However, it is notable that the number of Magistri has declined rather steadily since 2012, a trend that affirms Aneesh’s concern that fewer and fewer of Pingry’s faculty are holders of this prestigious distinction.

I decided it might also be interesting to see the differences in faculty retention across departments; I observed that the department that seems to retain its faculty the best is the arts department, which sees an average 5.47% of its faculty leave each year since 2012. By my metric, the language department seems to be the worst, with an average percentage at 11.04%, which doubles that of the arts department

While quantitative analysis can be informative, I do not feel it is sufficient to survey an issue as nuanced as teacher turnover solely by the use of statistics. In an effort to humanize my analysis, I spoke with US Director Chatterji, who was familiar with many of the recently departed faculty and could give me a more personal outlook on the issue. We talked first about the measures Pingry takes to incentivize teachers to keep teaching at Pingry. While she pointed out that Pingry has no formal incentivization program, she stressed the importance of “conversation” to faculty retention. She says that “teachers want to teach at Pingry because of its emphasis on human relationships.” She cited the numerous instances in which she had written recommendations for teachers applying for positions at other schools: by speaking about their experience and perhaps making a change to what they’re teaching, their office space, or the number of seasons they coach, these teachers were often happier and chose to continue teaching at Pingry, even with other job offers on the table.

She also made an important distinction between the types of departures, saying that “[Pingry] can’t hold all people. Our goal is not to retain people who are leaving because of retirement, marriage, or other life circumstances.” Instead, she believes that the more important number to look at is how many teachers are moving to other schools in pursuit of something Pingry wasn’t providing. Mr. Karrat or Dr. Chin-Shefi are examples of teachers who could fall into this category. Looking at departures from this lens, there does not seem to be a trend or major issue, with an average of 2.5 faculty moving to different schools each year and the rest leaving for largely unpreventable reasons.

The third category of departures is dismissals. While often the most dramatic and memorable, this is the category over which Pingry has the least control, as the school cannot control the behavior of its faculty. Nonetheless, I chose to look into an area where Pingry can exert at least some influence over the frequency at which they are forced to dismiss teachers: the hiring process. Ms. Chatterji explained that Pingry posts job openings in various locations, including job search websites, as well as on the “Employment” page of pingry.org. Mr. Dinkins, and now Ms. Holmes-Glogwer, in collaboration with department chairs, then sorts through resumes and applications from these various channels to identify qualified candidates. If the number of dismissals is actually an issue, which I don’t have the data to conclude (the Record does not write departing faculty articles for dismissed faculty), perhaps Pingry is losing its ability to attract candidates who, once hired, can continue to uphold the standard that Pingry expects from its faculty. Eva Schiller (V) also mentions that “there seems to be very extreme punishment for certain teachers without widespread preventative measures being made across the board,” and I concur that clearer guidelines for faculty conduct might help reduce the number of necessary dismissals.

Ultimately, though, I believe this investigation indicates that the Pingry administration seems to be doing their best to retain faculty. As the statistics I gathered show, recent concern likely stems from last year’s unusually high departure rate, and while the number of Magistri does seem to be declining, there is no way to say it will not rise again in the near future. At the same time, teacher turnover is an important issue to monitor, and investigations like this one can allow us to hold the school accountable if an abnormal teacher turnover rate begins to more conclusively tarnish the Pingry experience.

In the wake of this devastating COVID-19 outbreak, a lot of people have felt a sudden urge to do something, anything, to help the community heal. Even though making a thank-you video or doing a color-a-smile seems pointless next to the tragedies we face, these initiatives make a difference. As Oscar Wilde put it, “The smallest act of kindness is worth more than the grandest intention.” The amount of time it takes to post on Instagram is the same amount of time it takes to fill out the form that sends notes of appreciation to the healthcare professionals at Morristown Memorial. Though we cannot provide a cure, there is no end to the ways we can support the people in our community. Pingry’s Community Service Council has started making Morning Meeting announcements that present volunteer opportunities from sharing your appreciation to making sleeping mats out of plastic bags. We urge you to at least look at the slides, if nothing else, to learn about what is available. It is easy to feel helpless in this socially distanced time, but we can assure you that even one thank you video will bring a smile to a doctor who has worked around the clock, or calling your grandparents every so often could truly brighten up their day. When we get out of this quarantine, I think it would be amazing if every student could come back to Pingry knowing they brought a smile to just one person’s face.

By Eva Schiller (V)

A metapoem is a poem about poetry. The poem, somehow, has crossed the fourth wall and recognized itself as a sequence of words and letters. It can then evaluate itself, and even criticize itself. Think of this article as something of a meta-article: an article about articles. Specifically, an article about the credibility of the Pingry Record. Are we openly and accurately reporting Pingry news, or have we––as my title indicates––gone soft?

Perhaps I should clarify what it means to “go soft.” I define it as ignoring relevant topics for the sole purpose of avoiding controversy and protecting the Pingry ‘brand.’ I should also clarify that the Pingry Record is not, nor has it ever been, an organ of the administration. All content and all editorial decisions come from students and faculty advisors. As Dean Chatterji informed me, “the administration does not provide input into what the Record covers.”

Nonetheless, based on issues from the last fifteen years, the Pingry Record is undeniably more conservative than it used to be. The following are examples of controversial and problematic topics found in old issues, all of which I believe are not appropriate for a 2020 issue.

1. An opinion piece called “The Real Zero Tolerance Policy,” which appears on page three of the January 2003 issue. The article, which is publicly available on the Pingry website, discusses racial issues at Pingry, as well as political correctness and racist politicians. It takes just one quick skim of the article for a modern day reader to spot multiple points of contention. In addition to its subject, the piece includes biting quips about racial inequality, as well as racist statements (written ironically) and uncensored racial slurs. Clearly, this is in no way acceptable for a 2020 issue, nor should it be. However, it certainly demonstrates just how significantly the culture of Pingry, and by extension, the Record, has changed in past years.

In addition to publishing controversial articles, older issues of the Record report a coarser version of Pingry news.

2. The April 2004 issue dedicates a front page headline to the news that “Financial Aid Funds Will Not Meet Students’ Need.” An editorial on page two, and two additional articles on page four further explore the problem and criticize the “moral message… the school [is] sending if qualified applicants cannot attend Pingry due to financial need.”

3. The April 2004 issue also includes a rather harsh letter from former Assistant Headmaster Adam Rohdie, who “…ask[ed] the editors to rethink what is at the core of Pingryʼs Honor Code.”

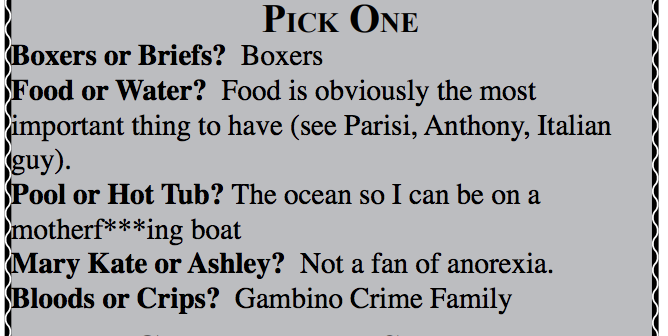

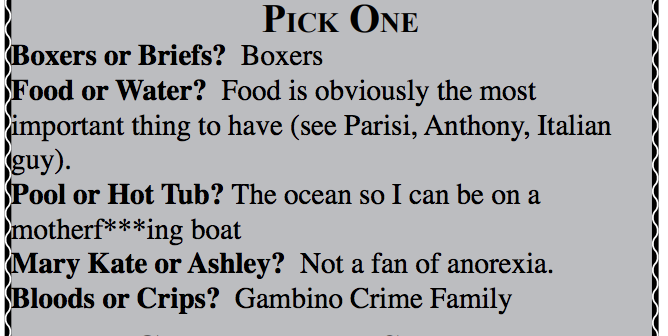

3. The April 2009 issue includes a student interview featuring expletives and a joke about anorexia (in response to the question: “Mary Kate or Ashley”).

It is important to note that the aforementioned cases are not consistent with every single article and issue published during these years. As Student Body President Brian Li (VI) noted, “the content of the paper ebbs and flows as leadership transitions from year to year.” However, I chose to highlight the most controversial articles because they set the previous limitations of the Pingry Record. Topics that were once considered in bounds are now considered out of bounds, making it difficult to deny that the Record has developed into a “softer” establishment.

This could be due to a number of reasons: cancel culture, increased awareness of diversity and inclusion, and rising political polarity have found their way into Pingry and beyond within the last ten years. As a result, we all have to be more conscious of how our actions affect others, and the Record has come to reflect that. Just this year, the editorial staff took steps to ensure that our opinion remained neutral on difficult topics such as teacher-student relationships. As an editor, I can attest that other hot topics––TikTok Honor Code violations and racial slurs still floating around on campus––are also, by some unspoken rule, not within the bounds of Record material (ironically, in mentioning them, I run the risk of crossing that boundary).

That said, a softer Record is not necessarily a bad thing.

The internet age puts us all in the spotlight, amplifying the impact of small actions that would have gone unnoticed pre-social media. This makes the new decade a difficult time for daring or accusatory articles. A kinder and gentler Record could perhaps indicate that “students are more considerate of the community, and how their words might impact those around them,” Dean Chatterji points out.

Of course, I in no way advocate the curses, racial slurs, and insensitive comments I found in older issues of the Record. However, the candor of the content I cited, despite fostering controversy, did increase its appeal and create a genuine time capsule of the Pingry community. I respect those articles for their openness. At the end of the day, the Record staff has the power to impact the opinions of the Pingry community, and if we can’t discuss hard topics openly, nobody will. Thus, as an editor, I feel it is our responsibility to learn from past articles and recapture their candor, while still retaining a higher level of cultural respect. If we do so tactfully, we could paint a more raw and genuine picture of Pingry.

By Christine Guo (IV)

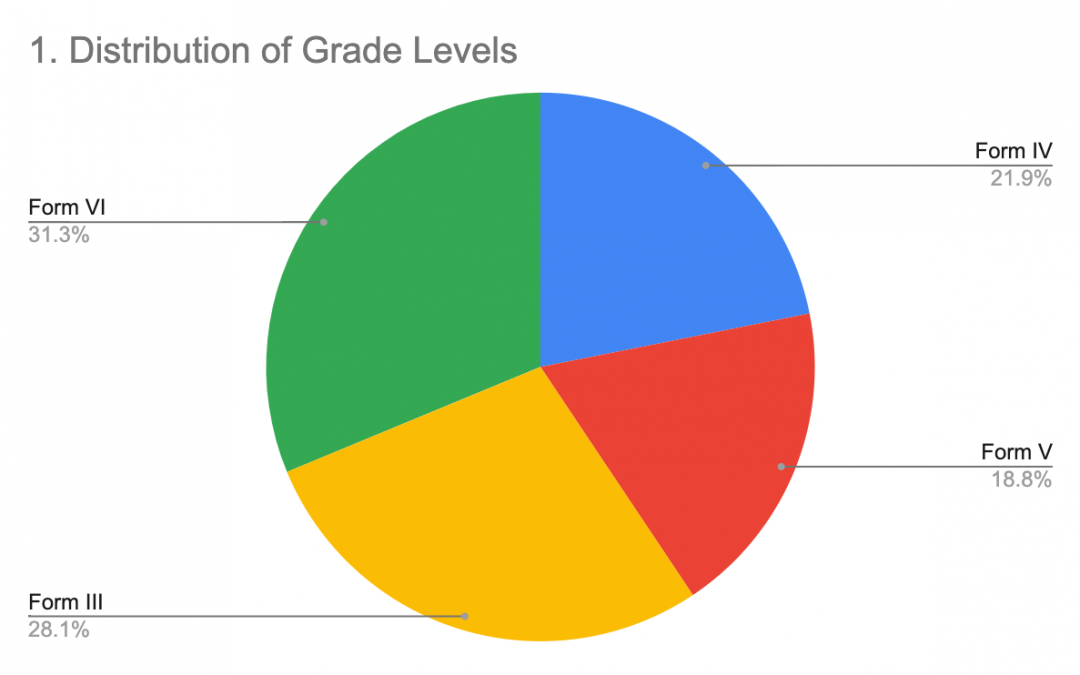

The Pingry Record recently sent out a survey to 75 Pingry Upper Schoolers about the school’s academic life. The purpose was to see what aspects of the school could be improved upon from a student’s perspective. Because it was anonymous, students were able to speak out on certain subjects that they may not have felt comfortable discussing before. The information gained from this survey benefits not just students, but the entire community by creating a better learning environment.

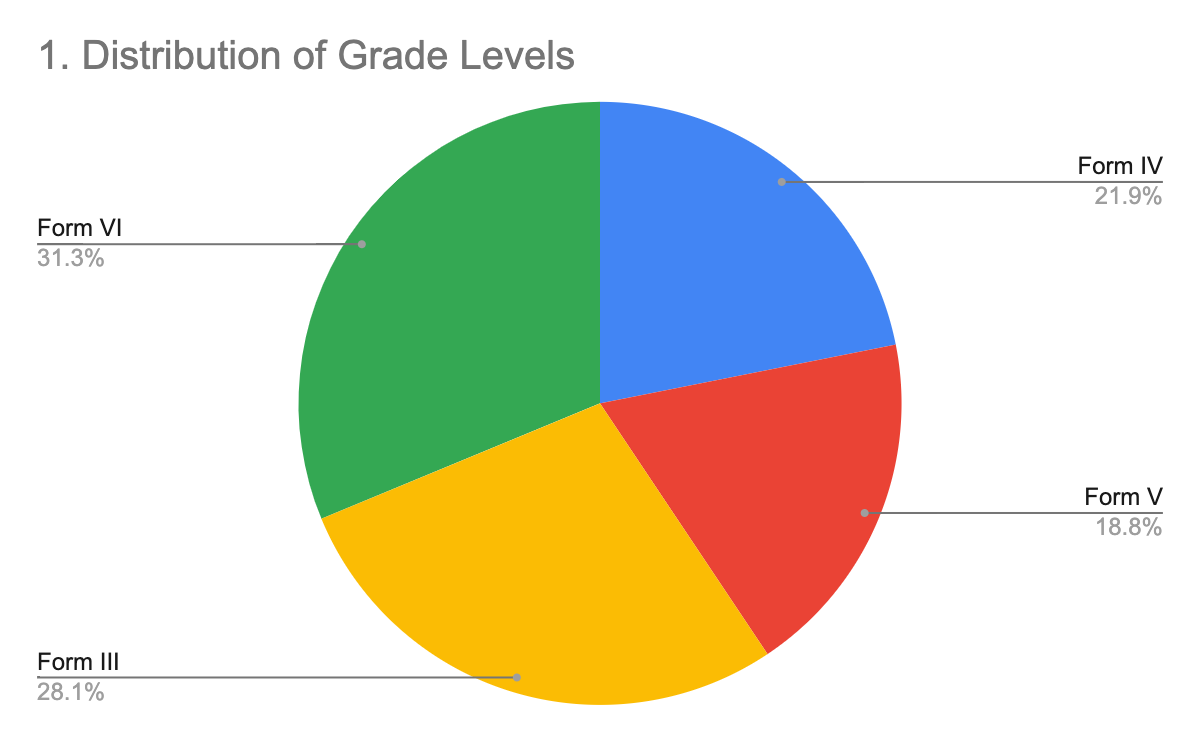

To get better results, it was crucial to poll a wide variety of Upper School students. Even though the juniors and seniors may have more experience in course selection, it was ultimately decided that every grade level should have a chance to voice their opinion. However, because the survey was only sent out to a small percentage of high schoolers, the data is not as accurate as it would have been if the entire school was polled. Moreover, only 32 people answered the survey, so the data cannot be considered a perfect representation of the student body. Luckily, a similar amount of people took the survey in each grade (Graph 1).

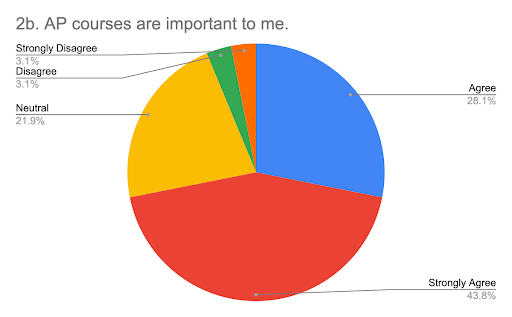

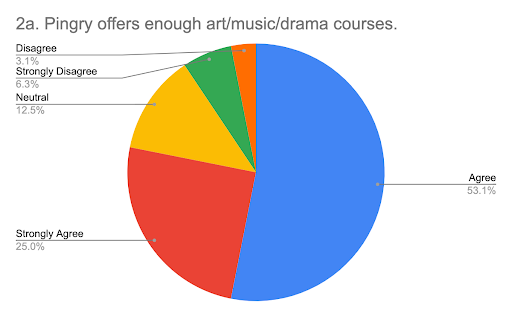

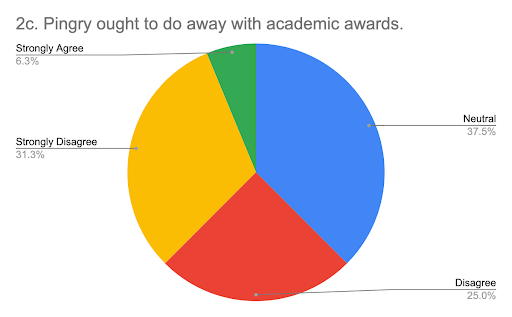

The majority of the survey questions were answered on a “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” spectrum. Overall, there were some very interesting results. The majority of students agreed that Pingry offers enough art/music/drama courses (Graph 2a). In another statement, the majority strongly agreed that AP courses are important to them (Graph 2b). This is intriguing because it shows how relevant and worthwhile AP courses are to Pingry students. Most also felt neutral or strongly disagreed with the statement that Pingry should do away with academic awards (Graph 2c). However, in a later statement, the majority agreed that Pingry focuses too much on academic success (such as grades) (Graph 2d). Even though the results from Graph 2d and 2c may contradict each other, it is clear that many still see the academic awards as an integral part of the school. Lastly, more than half of the students disagreed that their teachers use Schoology effectively to send them updates (Graph 2e). This data shows how there is still a need for improvement with how technology is used in the classroom, which is especially relevant during remote learning.

The last few questions on the survey were free response. One question asked students whether there were any specific courses that they wished the school offered. A handful of students wanted more finance classes, especially those that could be applied to real-life circumstances (such as doing taxes). Other students wanted more philosophy and psychology courses. Another question asked if there were any extracurriculars that students believe the school should fund/pay more attention to. Some people wanted more attention towards debate, while others wanted funding for the music equipment and set design tools. However, it is important to also note that the majority of surveyed students did not offer a response to these questions.

After reviewing these results, one impressive takeaway is how content students are with the school’s academic program. That said, there are definitely ways to improve the student experience at Pingry.

By Noah Bergam (V)

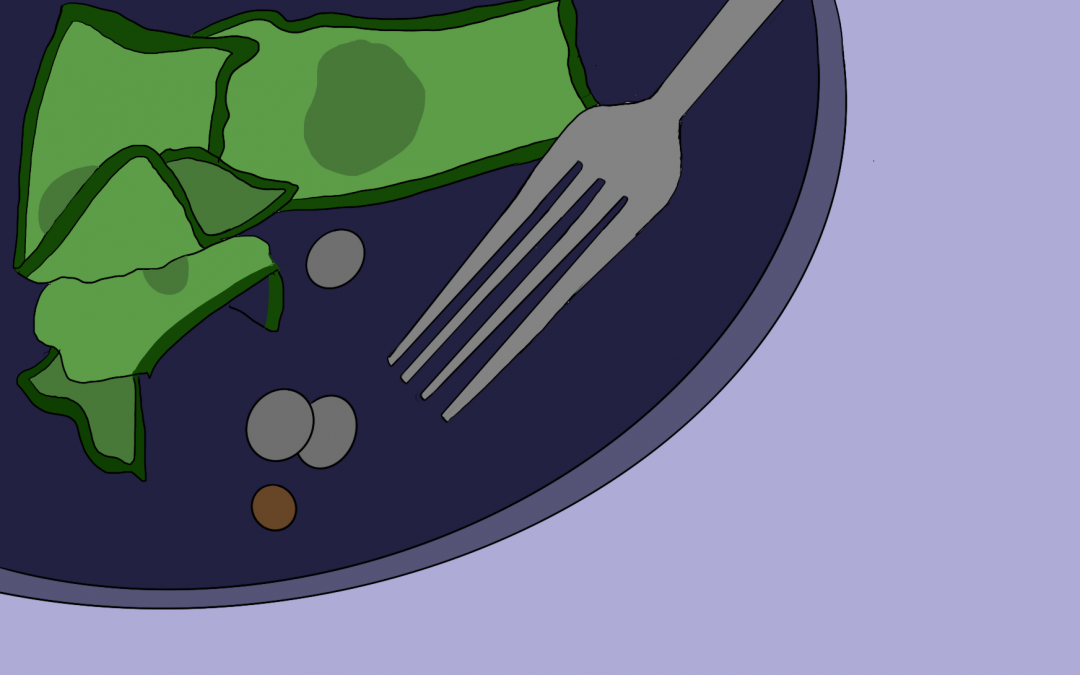

The Pingry tuition for the 2019-20 school year was $42,493. Lunch cost $1,378. Those are significant numbers in my life, numbers that, for over six years, have hovered over my head, acting as a reminder of what doesn’t go to my younger siblings each year.

Those numbers are especially relevant in the era of remote learning. Assuming the very likely scenario that the rest of the school year is remote, it appears students are on track to lose out on both tangible and intangible aspects of an expensive educational experience. This problem, of course, isn’t unique to Pingry. Many universities have issued refunds on room and board and meal plans in the wake of this change. I believe Pingry ought to follow suit and prorate our SAGE Dining meal plans––and while it is unlikely that we could receive a partial refund on the less quantifiable intangibles that we lost this year, it’s a conversation worth opening up … especially if this remote learning situation continues into next fall.

I remember back in seventh grade when some friends and I tried to break down the cost of Pingry life into an hourly rate. It came down to about $30 an hour, and we joked about how much we were getting robbed by DEAR time––but even back then I think we understood this metric wasn’t the end-all-be-all. The years since have only affirmed that for me: in a normal Pingry hour, you’re getting a lot more than what’s on the schedule. In fact, I would argue that most of Pingry’s value comes down to the stuff you don’t expect: the triumphs and the failures, the conversations, the relationships, the journey as a whole. We cannot and should not try to assign dollar values to those kinds of experiences.

Such is the paradox of the educational product: for students, the beneficiaries, Pingry is a priceless experience, but for our parents, the customers, it is a hefty investment with a fairly clear goal: “success” in a high-quality educational environment. In my experience, the student and parent perspectives mix like oil and water––where the external parental perspective sees a clear-cut result, the internal student perspective sees the fruits of a complicated learning process.

The issue we now face critically disrupts the learning process and the experience as a whole, which makes it much easier for students and parents alike to take a critical stance on Pingry as a product. Of course, we are fighting it. We are trying our best to believe in the intangibly valuable educational community, and to an extent, we’re succeeding … but at the end of the day, Google Hangouts can’t replace the little things that make real school real: the fast-paced conversation of class, the small talk with teachers, the time with friends, the work-home separation. A screen can’t project all those priceless dimensions of the Pingry experience.

But can we prorate the priceless? Can we somehow reimburse students for the intangible education that they lost, while still keeping faculty paychecks running? The answer, especially in the wake of this unforeseen disruption, is probably no. Neither universities nor private high schools have even entertained the concept, citing the argument that, despite the drop in quality, they are still doing their best to provide educational resources remotely. That being said, if school is unable to resume in the fall, that changes the game, since tuition adjustment would be an act of foresight on behalf of a “new” product rather than an after-the-fact reaction in the midst of chaotic change.

In any case, there are two requests we as students can and should make, in the event that remote learning extends to the rest of this year and potentially beyond.

The prospect of refunding some portion of school costs is a matter of goodwill and care for the community. It is the kind of action that recognizes the state of our education not only as a journey in life but as a financial investment that ought to be respected.

“You shouldn’t go outside without pepper spray,” my dad tells me over lunch.

“Nothing is going to happen,” I say.

“Just be careful.”

I sigh, grab the small canister of Halt! that sits on my desk, and exit the house for my quarantine walk. I feel safe, because I know my new neighbors across the street are Asian-American, and so is the other house five doors down. There is a new house being built on the next street over and the new family stood outside their house admiring the construction, and I smile at them. However, the owners of that new house are not as kind, and throw me one of the nastiest looks I think I have ever seen.

I feel the can shift around in my jacket pocket.

I then see a mother walking with her children and a dog, and then one of the other neighbors steps out of her house with her dog, joins the mother and her children, and gives them each a hug. I laugh internally, thinking that they are breaking social distancing rules, but just as they noticed me they moved to the other side of the street. I tried not to notice the occasional glance back from the two adults.

I don’t take that route anymore when I walk by myself. An overreaction? Maybe. I don’t think they’re going to hurt me. I just don’t want to have to go through that again. The shame, the feeling that I need to somehow cover my face. These thoughts have become my new norm.

I have always believed in activism and utilizing our freedom of speech to speak up about topics which are important. While I have been lucky enough to be able to avoid the violent discrimination resulting from the coronavirus toward Asian-Americans, I’ve been pretty vocal about some of the hate crimes that have happened to members of my community, as well as the wider Asian community worldwide. There was the stabbing of a Burmese family in a Sam’s Club; a gun drawn at a Korean university student who had confronted someone for posting coronavirus pamphlets on his dorm room door; man killed as a result of suspected foul play from his neighbor; people beat up in Philadelphia and New York City for not wearing a mask; and the ones who got beat up for wearing one. Unfortunately, these instances only name a few examples.

Comments online about these hate crimes are dominated by people saying things like, “Wow, now you know how all the other minorities feel,” or my personal favorite, “You’re mad now that you got your honorary white person card revoked huh?”

This comment struck me. I think I always subconsciously felt it, but I feel like Asian-Americans aren’t always treated as people of color (POC) in this country. Rather, I view that we are treated as people of color when it is advantageous for a certain view, and viewed as beneficiaries of white privilege at other times. It’s why the system of affirmative action in universities goes against us, but also the same reason we are encouraged to “stand together as minorities” when other groups have their own activist movements. It’s also why politicians use us as a “model minority” for other minorities when those politicians cannot provide adequate support for broken systems.

A large part of this sometimes-POC sometimes-white-privilege dynamic stems from a certain Asian-American community wide unwillingness to “make trouble.” For instance, one of my Asian-American friends encountered a situation where a racist comment was made, and when I encouraged her to speak up, she said her parents didn’t want her to make trouble. This problem with being afraid of conflict is something I’ve heard countless times. It’s why a lot of the hate crimes that are happening now aren’t being reported on by major news media networks like CNN, MSNBC, or FOX. I feel like most of the country mistakes Asian-Americans’ unwillingness to bring about conflict with us not encountering any.

As a leader of the Asian Student Union, this time has brought many questions to me from other members of the community. “What should we do?” and “How do we stay safe?” are all things that younger students, and friends outside Pingry have asked me. I don’t have the answers, and part of me feels like I should as someone who is vocal about Asian-American topics. These aren’t questions I’ve had to ask myself until now. I started the ASU with my friends to enact dialogue and some shift in thought, even if it was just among members of our small Pingry community. I wanted to encourage my peers to recognize and stand up for discrimination, but most importantly to find the courage to stand up for themselves regardless of their identifiers. I never could have expected that the greatest test of my activism would come now. Suddenly, as if overnight, the sphere of these discussions have left the little safe haven that I have helped create in Room 310 at a small private school in Basking Ridge. They feel much more real now, which is scary at the same time as it is empowering. That call to action we’ve been waiting for, that spark that we’ve been hoping will ignite, finally came. It’s time for us to enact the change we wanted to see in our own communities.

I’ve faced a lot of criticism from those around me, those who think I’m being too vocal about the situation at hand, those who think my words aren’t constructive action against the crimes being committed. I’ve even been told that the racism that we are seeing as a result of the coronavirus is justified due to the horrible actions the Chinese government is taking against Africans in China. However, groups pointing fingers at each other is the thing that is least constructive. Racism is racism, no matter which group is committing it, and it should be condemned, not based on the political climate in which it takes place, but for the morals that we as a society have been trying to progress.

Justin Li ’21 is the Layout Editor of the Pingry Record. He joined as the digital editor for the Record’s new website during his sophomore year. While he has written articles in almost every section of the Record since then, he’s been drawn to exploring the teacher-student relationship at Pingry in his recent work. He finds great satisfaction in the seemingly tedious process of piecing together a page on inDesign and loves looking for new ways to keep the paper looking fresh. In his free time, he enjoys creative writing, playing the piano, and Taiko drumming.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

By Julian Lee (V)

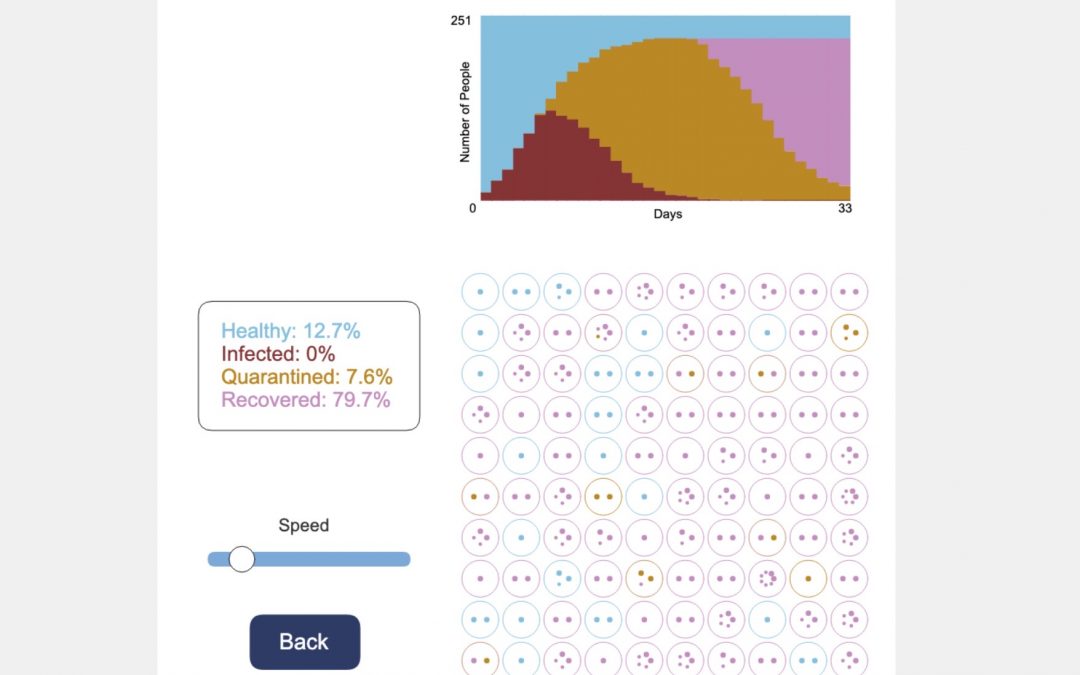

With statewide stay-at-home orders currently issued in at least 42 states, we should take into consideration the factors that could compromise the effectiveness of this quarantine. Inspired by the simulations created by the Washington Post and the YouTube channel 3Blue1Brown, I wanted to further investigate how human behavior––specifically, visiting friends––can impact the spread of COVID-19 under a quarantine environment.

I created a simulated environment of 100 households, where only interactions between family members and one-on-one visits with friends can cause infections. The user can change various parameters, such as the average days between visiting friends, and observe how changing these variables affect the spread of the virus. The simulation can be found here.

The simulation suggests that in the world of social distancing, the frequency of visiting friends has a greater impact on the spread of the virus than the size of a person’s social network (simulation results shown at the end of the article). Someone who visits the same friend every other day spreads the virus faster than someone who visits one friend every four days in a ten-person social network. Based on the simulation, reducing the number of friend visits during quarantine by a factor of two could have an effect comparable to halving the infection rate of the virus.

Below are my findings from the simulation (100 simulations were run for each setting):

While someone might think it is completely benign to visit just “one” friend every other day, such behavior by an entire population can still result in an exponential growth of the virus. For example, if someone infects the one friend they are visiting during quarantine, that friend would then infect their entire family, and these family members would infect their own friends.

This simulation helps to quantitatively demonstrate an obvious yet powerful fact about social distancing: to ensure that our quarantine proves effective, it is essential that we work towards minimizing the frequency of visiting others.

By Meghan Durkin (V)

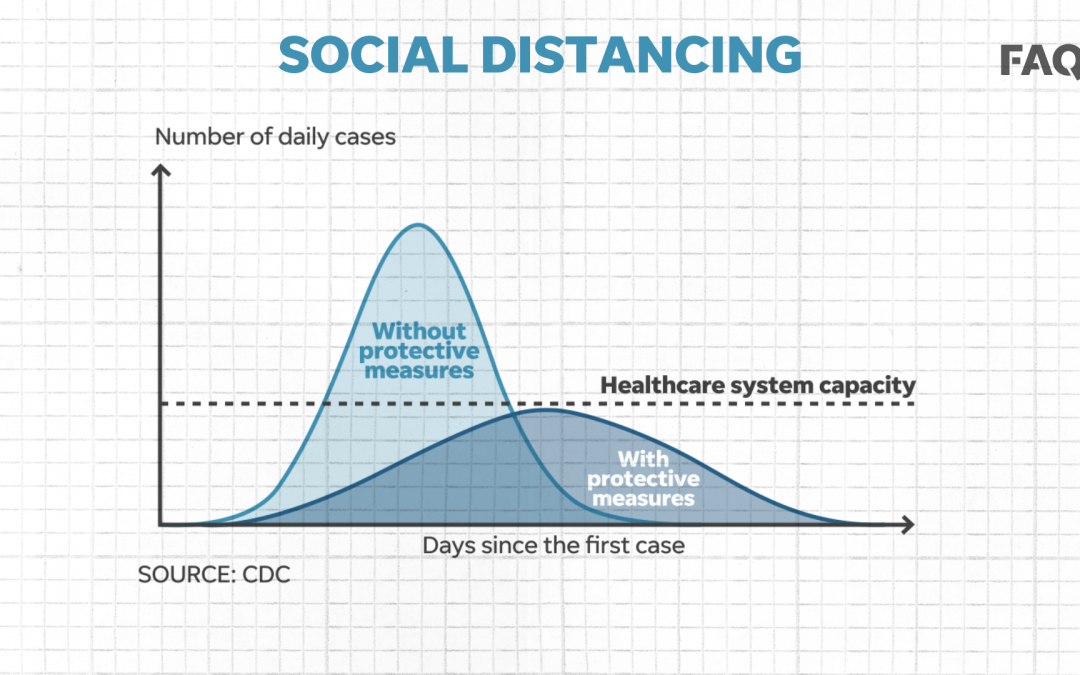

It’s been over two months since the United States confirmed its first coronavirus case in late January. Since then the landscape has changed drastically, as the virus has forced all non-essential businesses to shut down, kept most states under lockdown, and left most of the world at a standstill. This week, with cases in numerous states across America predicted to hit their peak, the healthcare system, its workers, and all others without the ability to stay home prepare for the hardest battle in the ongoing war against COVID-19.

During a news conference on April 4, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo called the apex “the battle of the mountain top,” and affirmed that New York and other highly-affected states, including New Jersey, “are not yet ready for the highpoint.” Our lack of preparation for such a high number of cases remains the greatest challenge of this apex. How can a healthcare system brace for a pandemic it never expected? How do hospitals continue to treat patients as their resources dwindle? As of April 11, the United States became the country with the greatest number of confirmed deaths, with over 1,000 being from New Jersey and about 7,000 being from New York. If the pressure on our healthcare system becomes too immense, those numbers will rise even faster.

Even when cases begin to decline, avoiding another outbreak is critical to curbing even greater disasters and preventing future quarantines. Many countries who seemed to have handed coronavirus an early and swift defeat faced a resurgence of cases in late March. For example, in Singapore, where cases had dropped by late February into March, a second wave of cases has forced the country to close all non-essential businesses and schools. The emergence of new cases in Singapore serves as an important warning to the United States: allowing people to return to school, work, or “normal” life too early may cause another outbreak of the virus. If the country doesn’t proceed with caution, there could be a second peak on its way.

Here’s the brighter side: a peak must be followed by a decline. At this point, a decline in cases can’t come soon enough. The Coronavirus is not only a medical problem, but also an economic disaster unlike any other. What had been a booming economy in the United States is now facing a major downturn. With many businesses forced to shut down, specifically those in the hospitality industry, companies have little choice but to lay off or furlough large parts of their workforce. In about three weeks, over 16 million Americans lost their jobs and the number continues to rise. For employees and employers across the country, the sooner the virus is controlled, the faster they can get back to work.

Ultimately, the onset of a peak in cases poses both problems and promise. The United States is far from being out of the woods, as evidenced by continued problems in countries, like Singapore, who are facing a second wave. Thus, the balance between caution and normalcy is becoming increasingly important to reduce deaths and keep the healthcare system afloat. Though, with the worst (hopefully) almost behind us, the U.S. and its people can slowly start to see the light at the end of the tunnel. If not released from possibly many more months under stay-at-home orders, then at least hope and reassurance that the worst is on its way out.

By Mirika Jambudi (III)

Due to Pingry’s transition to remote learning last week, students from all four grades were able to showcase their talent in Pingry’s first-ever Remote Talent Show! Over spring break, Student Government class presidents were hard at work redesigning the format of the competition using a March-Madness-style bracket. “We had to reorganize the entire bracket, but it ultimately allowed for more students to be able to display their talents,” said J.P. Salvatore (III), freshman class president. He described his excitement to see the talents presented and his hope that it would be a great community-bonding experience.

Students submitted a variety of talents, ranging from self-accompanied songs to skillful soccer ball handling. Out of the 11 submissions, the Upper School voted on their four favorite acts. The top 4 students advanced to the final round and were able to submit new clips of their talents. The four finalists were Sophia Cavaliere (V), Camille Collins (III), Natalie DeVito (IV), and Nicolás Sendón (III). All the finalists brought their best to the final round, and it was up to students to decide who would ultimately become the first-ever champion of the Remote Talent Show. “It was fun seeing the final four talents and voting … I was impressed by the amount of talent each grade has to offer,” said Ram Doraswamy (IV).

Ultimately, on Monday, Nicolás Sendón (III) was announced winner and Natalie DeVito (IV) earned runner-up. Nicolás had played a song on the bagpipes, while Natalie sang a song and self-accompanied on guitar. “I was excited to hear that I had won … everyone brought a lot of talent to the show, and I’m grateful for the community’s support,” Nicolás remarked. Natalie agreed, describing her gratitude for those who reached out to her. “Connection and solidarity is super important right now, and sharing art has the potential to bring people together, now more than ever,” she said. Nicolás was awarded a $20 Amazon gift card for winning first place. Congratulations to Nicolás and Natalie, and to all others who participated!

By Max Ruffer (Grade 6)

We hear a lot about the big picture epidemiological story of COVID-19: the way it spreads on an interpersonal or interregional basis. But what about on the cellular scale? As numerous institutions race to find a cure to COVID-19, they must consider how the virus behaves in our bodies––we should consider that too. So let’s take a step back and look at the virus that’s on a chaotic world tour: SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2 first attacks the upper and lower respiratory tract. Early stages of the virus show reduced white blood cells and lymphatic cells, considering these cells play a crucial role in the immune system. The fact that we’re working with a virus makes it even harder to cure. Unlike bacteria, viruses generally take over human cells and force them to make copies of the virus. The virus does this by landing on a human cell and injecting its genetic material into the cell. Antibiotics are not an option because they function by stopping bacterial reproductive systems––viruses rely on the host to reproduce (which is why they are often not considered living creatures). According to microbiologist Diane Griffin, “Bacteria are very different from us, so there’s a lot of different targets for drugs. Viruses replicate in cells, so they use a lot of the same mechanisms that our cells do, so it’s been harder to find drugs that target the virus but don’t damage the cell as well.”

The rapid rate at which SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses mutate also adds to the complexity of finding a long-term solution. These mutations “trick” the lymph nodes’ memory cells, which can remember and immediately launch an attack on a recurring virus if it reenters the body. However, once the virus mutates, the cells can no longer recognize the strain and must relearn its signature.

Thus, while an antiviral treatment might be effective one year, it may fail the next. For example, the reason you need to get a different flu shot every year is because the flu mutates every year.

Even with these disadvantages, humans are fighting back. Currently, 306 studies are being conducted into how SARS-CoV-2 behaves, but only nine have been completed. As of now, we have discovered only two drugs that may impact the disease: hydroxychloroquine and danoprevir combined with ritonavir. To accelerate the progress of finding a vaccine, many researchers have used their understanding of SARS, a virus similar to COVID-19, as a starting point. However, studies on medicine take about 11 months to complete in the United States and even with these existing treatments, COVID-19 remains deadly, killing many patients within 15 days.

The high infectivity of COVID-19 presents one of the most difficult challenges. Hospitals are running out of safety equipment, beds, and respiratory equipment due to the overwhelming number of patients with COVID-19. The lack of safety equipment is an issue for people who are at the front lines of this pandemic. When healthcare workers are infected, the virus becomes much more dangerous. Simply being near someone infected can give you the virus. As a result, the CDC now recommends wearing cloth face masks when out in public to slow the disease’s spread and thereby relieve the stress on the healthcare system.

Despite these difficulties, COVID-19 can be eradicated. With the help of “social distancing,” as well as the selfless work of researchers and healthcare professionals, humanity will overcome this crisis. As a community, we can do our part by staying inside and helping those who need it. Although COVID-19 may seem an insurmountable obstacle, we are slowly clearing it.

By Brian Li (IV)

With the closure of schools in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, students are unable to receive the same level of education as before. For Pingry students the changes have been especially relevant in the context of fast-paced Advanced Placement (AP) courses. AP courses are considered rigorous and demanding, and they usually finish with a three-hour year-end exam covering all of the topics studied during the course. However, as a result of school closures, many AP courses will not be able to cover all of the necessary curriculum, leaving students at a disadvantage for the exams.

To combat this issue, The College Board, the parent organization of AP courses, has altered the exams in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In place of the standard three-hour in-school exam, The College Board has announced that exams will be 45 minutes long, administered online, and only include “topics and skills most AP students and teachers have already covered in class by early March.” They will be open-book, with AP World Language exams consisting only of speaking questions and most others consisting only of free-response questions. The exams will be administered from May 11 through May 22, the third and fourth weeks of the month, and makeup exams will be offered in early June.

In these extraordinary circumstances, such significant changes to the AP exams may seem very sudden. Students with questions can contact their teachers or counselors, or visit the AP College Board COVID-19 website linked here.

By Alex Wong (I)

On March 31, 2020, the Middle School announced a brand new schedule. Effective April 6, it is very similar to the regular school schedule, where classes would be held according to letter days instead of according to weekdays. The changes it does make, however, have elicited a variety of responses from the Middle School student body.

Middle School students discussed the new schedule during the April 1 remote Advisory session. During the week of March 23, Middle School students only attended one core class per day, as well as advisory on Mondays and Wednesdays. The new schedule is very similar to the regular school schedule: seven different blocks (in contrast to the five core classes in the former remote learning schedule), with four classes per day, as well as a flex (featuring student interest clubs) and Independent Work/Athletics Block at the end of the day. Some students expressed concern over the increase of classes in an unfamiliar environment. Laura Young (I) remarked, “I think that the former schedule had too few classes per day, however, the new schedule may be a bit much.” On the other hand, some students liked the increase of classes. Claire Sartorius (I) mentioned, “I think the new schedule is better because it feels like a regular school day.” Max Ruffer (6) mentioned, “I think that the new schedule will help with homework management. With the new schedule I only get the day’s homework. Getting a week of homework has messed up my eating schedule. When I do my homework, I try to get all the work done at one time. If I have a lot of homework then sometimes I end up doing things I normally would not do such as skipping lunch. With the new asynchronous classes however, it will help the students to improve skills such as writing before a major test.”

Middle School teachers hope that the new schedule will bring back a sense of familiarity to the whole Middle School. When asked about the new schedule, Middle School Dean of Student Life Mr. Michael Coakley said, “The hope with this new schedule, ‘Remote Learning 2.0’ as we’re calling it, is that we’ll be able to give students increased structure and community facetime in these unusual times. Connection with other people matters right now; it reminds us that our community is bound less by a building and more by the values and willingness to support one another that we all share.” Science teacher Ms. Debra Tambor is also optimistic about the new schedule, mentioning, “The modified remote learning schedule will allow for increased contact for students and faculty, the advancement of learning, and more structure to the student’s work week.”

In summary, the Middle School schedule has brought a lot of uncertainty to the table, for teachers and students alike. However, there is one thing everyone can agree on in the Middle School: we will get through this, and we will make it work.

By Alex Wong (I) The effects of COVID-19 are a lot clearer than the causes. It has closed schools and businesses worldwide, infected over a million people, and is seriously challenging the capacity of our healthcare systems, both here in America and abroad. But how did this happen? Almost everyone can agree the virus originated in Wuhan, Hubei, China … but how? There are two major theories.

The first is that it came about naturally and, according to Dr. David Lung,“was a product of […] excessive hunting and ingesting wild animals, inhumane treatment of animals, and disrespecting lives.” Animals such as bats, dogs, monkeys, and pangolins are often consumed as food, a very common practice in Mainland China. After some genome sequencing, it was determined that the Wuhan coronavirus and the bat coronavirus RaTG13 were 96% similar in terms of genome sequencing. According to an op-ed written by highly acclaimed Hong Kong epidemiologist Yuen Kwok Yung, who in 2003 helped Hong Kong fight the SARS virus, “This particular virus strand was obtained and isolated from Yunnan bats (Rhinolophus sinicus), and bats are believed to be the natural host of this Wuhan Coronavirus.” However there would need to be an intermediate host to get from bats to humans. The Wuhan coronavirus was 90% similar to a strand of pangolin coronavirus in genome sequencing, making the pangolin a likely (but not confirmed) intermediate source. However, because the Chinese government shut down the wet market where the virus was said to have originated, scientists and epidemiologists have been unable to obtain samples from the wild animals in the market, meaning no one yet has been able to confirm which animal it came from, or whether it did come from the market.

The second theory is that the Wuhan Coronavirus was created in the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) and accidentally set loose via an infected bat. The WIV has a history of researching coronaviruses, and in 2015 the Institute even made a bat coronavirus that could infect human cells. This artificial virus was very similar to SARS (a different coronavirus with symptoms similar to COVID-19). Additionally, the history of viruses escaping Chinese labs (such as the infamous 2004 Beijing SARS outbreak caused by the SARS virus escaping a government lab not once, but twice) have added suspicion. To be clear, the scientists were trying to figure out a cure to SARS, and did not have malicious intentions. However, according to leading microbiologists, the complexity of COVID-19 points strongly to origins in nature. Additionally, the WIV has released no research on coronaviruses since 2015. Ultimately, the theory that COVID-19 was made in a lab is based mostly on mistrust of the Chinese government, a mistrust most prevalent in the conservative discourse of the Western world.

Whether this was a natural virus or a man-made virus, one thing is evident: the Chinese Communist government could have taken quicker action to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Chinese doctors such as Li Wenliang, who later succumbed to the virus and tragically died, were actually given a notice by Wuhan police to stop spreading “misinformation” about a new “SARS-like epidemic” in December. As the spread continued, the Chinese government locked down Wuhan, but by then it was too late. A Chinese New Year gathering of more than 40,000 people has been pinpointed as one of the events that helped increase the spread within Wuhan. Furthermore, the Chinese government refused to take further steps to contain the virus until January 23, a full month-and-a-half since the discovery of the virus, this was not until nearly 5 million people had fled Wuhan before the lockdown. However, as the virus spread to other parts of the world, many other governments were caught off guard, and in some cases were slower to act on quarantining and testing than China.

The Chinese government has been accused of not releasing the full number of cases in Mainland China. Instead of classifying a death as “coronavirus death” they would classify it as “pneumonia-related death.” On top of that, Chinese health officials refused to give information about Patient Zero from Wuhan, and did not allow international research teams to gain access to Wuhan to try and find the origin of the coronavirus.

The Asian community across America has also been impacted by the coronavirus. Co-head of Pingry’s Asian Student Union Monica Chan (V) remarked, “The Asian community around the world has faced devastating repercussions of the virus, being targets of xenophobia and racism. There has been a surge in hate crimes against people of Asian descent worldwide, including vandalism, armed assault, and even mass shooting threats. It is important for the Asian community to remain careful at this time and stay safe!” When asked about what the Asian Student Union did to help fight back against the virus, Monica Chan (V) and Guan Liang (V) mentioned, “ We arranged a Dress Down Day before spring break ended to raise money for NGOs in China. We ended up raising $405 between the Middle and High school! We have also been staying home, social distancing like most people in our community. The Chinese parents within the Pingry community have organized a task force that collects and donates medical face masks to local hospitals with supply shortages. These initiatives are crucial for combatting against coronavirus as they unite the strengths of different ethnic communities.”

As the old adage goes, “History will always repeat itself.” Ineffective measures and misinformation by the Chinese government were on display back during the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak, and similar mistakes resurfaced in the early handling of COVID-19. However, we need to be careful in how we analyze the causes of this virus––the Chinese government certainly deserves blame, but we ought not to convert such frustration into racially targeted sentiment.