Apr 17, 2020 | COVID-19, Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

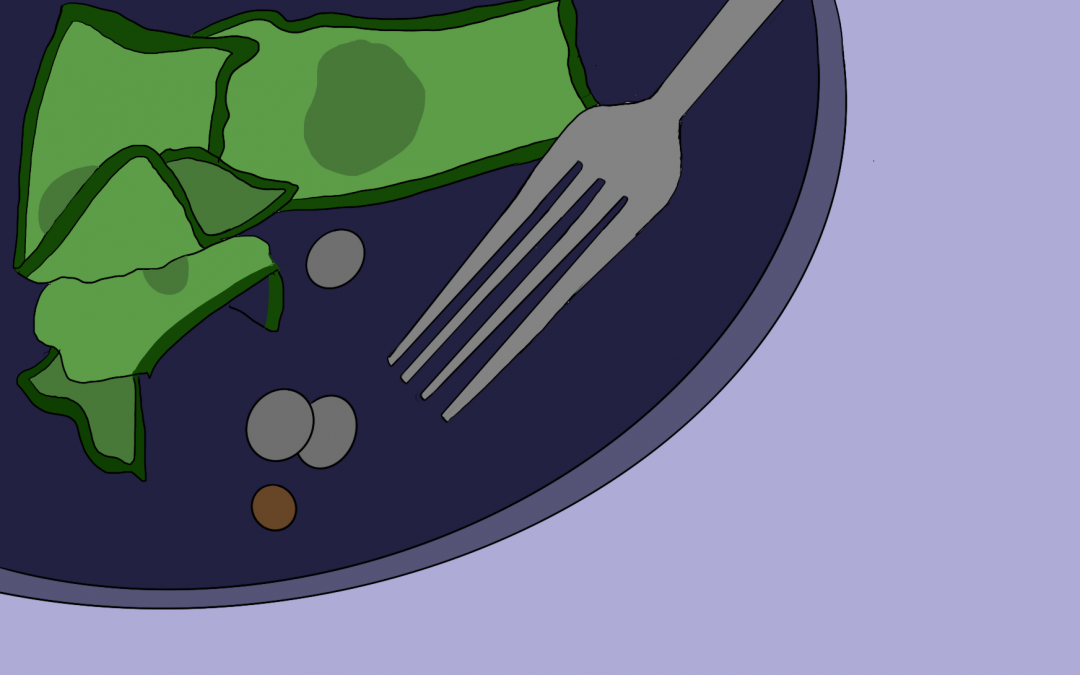

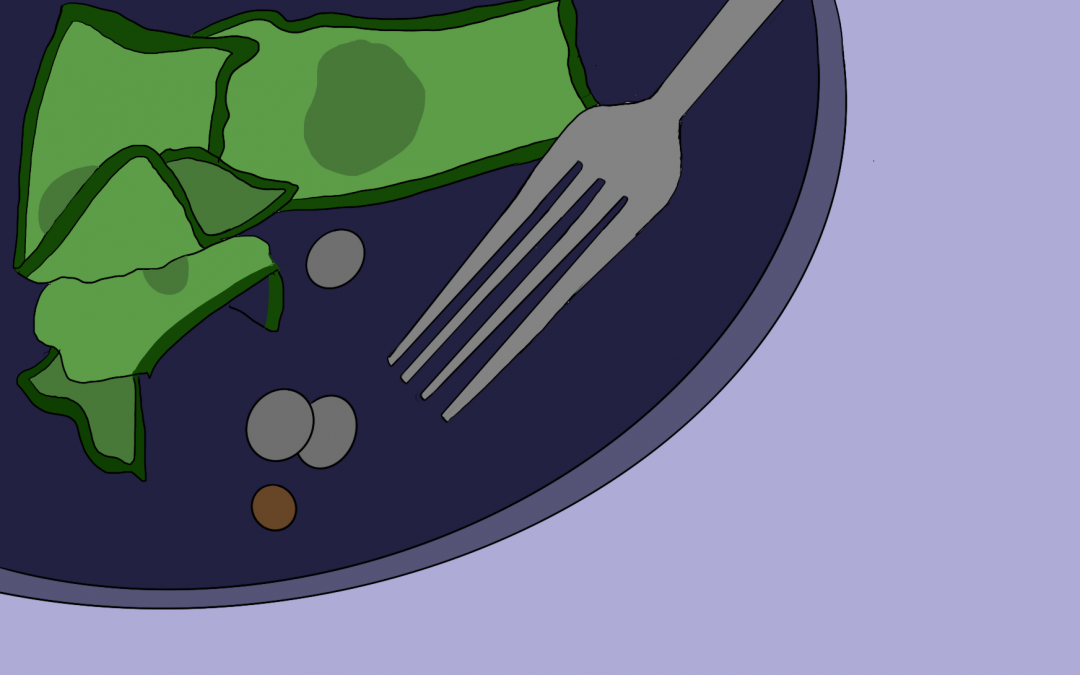

The Pingry tuition for the 2019-20 school year was $42,493. Lunch cost $1,378. Those are significant numbers in my life, numbers that, for over six years, have hovered over my head, acting as a reminder of what doesn’t go to my younger siblings each year.

Those numbers are especially relevant in the era of remote learning. Assuming the very likely scenario that the rest of the school year is remote, it appears students are on track to lose out on both tangible and intangible aspects of an expensive educational experience. This problem, of course, isn’t unique to Pingry. Many universities have issued refunds on room and board and meal plans in the wake of this change. I believe Pingry ought to follow suit and prorate our SAGE Dining meal plans––and while it is unlikely that we could receive a partial refund on the less quantifiable intangibles that we lost this year, it’s a conversation worth opening up … especially if this remote learning situation continues into next fall.

I remember back in seventh grade when some friends and I tried to break down the cost of Pingry life into an hourly rate. It came down to about $30 an hour, and we joked about how much we were getting robbed by DEAR time––but even back then I think we understood this metric wasn’t the end-all-be-all. The years since have only affirmed that for me: in a normal Pingry hour, you’re getting a lot more than what’s on the schedule. In fact, I would argue that most of Pingry’s value comes down to the stuff you don’t expect: the triumphs and the failures, the conversations, the relationships, the journey as a whole. We cannot and should not try to assign dollar values to those kinds of experiences.

Such is the paradox of the educational product: for students, the beneficiaries, Pingry is a priceless experience, but for our parents, the customers, it is a hefty investment with a fairly clear goal: “success” in a high-quality educational environment. In my experience, the student and parent perspectives mix like oil and water––where the external parental perspective sees a clear-cut result, the internal student perspective sees the fruits of a complicated learning process.

The issue we now face critically disrupts the learning process and the experience as a whole, which makes it much easier for students and parents alike to take a critical stance on Pingry as a product. Of course, we are fighting it. We are trying our best to believe in the intangibly valuable educational community, and to an extent, we’re succeeding … but at the end of the day, Google Hangouts can’t replace the little things that make real school real: the fast-paced conversation of class, the small talk with teachers, the time with friends, the work-home separation. A screen can’t project all those priceless dimensions of the Pingry experience.

But can we prorate the priceless? Can we somehow reimburse students for the intangible education that they lost, while still keeping faculty paychecks running? The answer, especially in the wake of this unforeseen disruption, is probably no. Neither universities nor private high schools have even entertained the concept, citing the argument that, despite the drop in quality, they are still doing their best to provide educational resources remotely. That being said, if school is unable to resume in the fall, that changes the game, since tuition adjustment would be an act of foresight on behalf of a “new” product rather than an after-the-fact reaction in the midst of chaotic change.

In any case, there are two requests we as students can and should make, in the event that remote learning extends to the rest of this year and potentially beyond.

- For the Board of Trustees: please prorate our Sage Dining meal plans. If we are not receiving a service that our parents paid for, we deserve reimbursement. In addition, please consider the prospect of “prorating the priceless,” for both this semester and, if need be, next semester––even if other institutions have dismissed this idea, it is certainly worth deducing and communicating its viability.

- For Mr. Levinson: please address both parents and the student body on this topic. Tuition matters, and in times like this, when the product of Pingry is being tested in unforeseen ways, it ought not to be taboo.

The prospect of refunding some portion of school costs is a matter of goodwill and care for the community. It is the kind of action that recognizes the state of our education not only as a journey in life but as a financial investment that ought to be respected.

Mar 29, 2020 | Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

Lights. Silence. 390 seconds of glory.

Ever since I first watched in sixth grade, I knew I wanted to do LeBow.

From the win of Katie Coyne ‘16 to the two-year reign of Rachel Chen ‘18 to the triumph of Miro Bergam ‘19, I sat anxiously in the audience year after year. I was the nervous yet critical viewer, who, in his endless deification of the stage, kept imagining how he himself might fare or fail in front of 700 academics. Time flew like an arrow, from imagination to reality. In my sophomore year, I took the stage with a speech about memes. And I won.

The aftermath followed a rapid progression from satisfaction to excitement to terror. I achieved what I had dreamed of for years, and I could still look forward to another chance at the stage in 2020. But I also knew I could very easily fail that second chance and fall short of the high expectations.

In preparing for this year’s competition, I believed that the only way to successfully replay the game would be to break it. So I chose to call out the unsettling pattern of universal agreeability that LeBow speeches were developing, a problematic pattern I myself upheld the year before. In this sense the speech was a critical self-reflection––I chose to burn the magic that I had internalized and glorified over the years, and from those ashes construct an argument against the very anti-argument nature of Pingry culture I embraced.

Did I fail? Certainly in the sense of losing the title.

But in retrospect, I got what I asked for. I did not design my speech to maximize likability among a judging panel––I wrote it in order to spark critical thought and disagreement among the broader student community. And in that sense, I think it was a success.

I met two counterarguments that, in the spirit of debate, I want to address.

To reiterate, my thesis is as follows:

“In order to make sure students develop the key skills of political disagreement, we ought to bring timely, wholehearted, messy debates into the classroom––and then we students ought to embrace more of that argumentative style in our own independent endeavors [eg LeBow itself].”

1. My message is NOT that Pingry students lack the capability to have difficult discussions. I can’t speak for what goes on within specific environments like affinity groups. I simply question how far-reaching, especially between identity boundaries, these discussions are. Thus, I assert that the humanities classroom is the best place to make controversial discussions informed and ubiquitous. Otherwise, Pingry students, like most citizens, will naturally flock to echo chambers, and schoolwide communication, especially in assemblies, will continue to favor numbing agreeability and “political correctness.”

2. Yes, I do think teachers should give their personal opinions in class. Obviously, this comes with a two-pronged expectation of maturity. The student should be able to respect the teacher’s opinion without bowing down to it, and the teacher should be able to be subjective with the explicit intent to inform rather than directly convince.

As I defend this thesis, I don’t pretend my speech was perfect. I made plenty of miscalculations, the most obvious of which was the exclamation that “I’m the Big Fish in a Little Pingry Pond!” Yes, that sounds arrogant. I was trying to be ironic, I was trying to make it clear that the concept of a big fish here is a dangerous illusion that limits one’s ability to think outside the scope of this community’s limited discourse. But I suppose using such a phrase as the cornerstone of the speech might have given some pretty negative impressions. So it goes.

It’s over now. Now I will return to the audience for one last year to watch the brilliance of LeBow from a new lens. But I won’t forget the message I crafted. I’ll continue to defend it and live it out, especially in regards to this newspaper.

The theory of the Big Fish was refuted. But defeated? The point was made on stage and proven offstage. So I accept this loss wholeheartedly.

Dec 9, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

When I was a little kid, I got angry when I heard my name. Noah. I heard the word ‘No.’ Somehow that just pushed me over the edge. My older siblings, realizing my dislike, would further taunt me by calling ShopRite ShopWrong. I would cry.

Now it’s more sophisticated. I cry a little inside when I see political arguments and platforms supported fervently in the negative.

Ralph Ellison’s anonymous namesake Invisible Man asked a simple question. “Could politics ever be an expression of love?” The quote reads quickly in the context of the chaotic unfolding of the novel. But when I read it, I stopped and realized this combination of words is powerful.

It comes back to me every month for the Democratic debates. As I’ve watched these candidates give their heartfelt pleads for their causes, I’ve gone through my own little evolution as a viewer.

When I first watched in June, I was amazed by how eloquently they all could speak, swinging from topic to topic with such ease and intensity. Each candidate presented their own style, playing different gambits and spinning sophisticated responses, tying it back to their audience. All on the spot. It blows me away. But … but what? The charm blurred with repetition? The candidates are all a bunch of phonies? Emails!? Perhaps. But the fundamental issue I see is not with any of the specific values they hold or policies they endorse. It’s about a frame of reference. Their tendency to express their stances in terms of the partisan negative rather than the general positive. The tendency is captured by the standby:

“I’m the candidate that can beat Donald Trump.”

There’s a use for this phrase in moderation. But it ought not to become a cornerstone argument of the party—2016 is proof that doesn’t work.

When this mindset of opposition takes over for a few questions, the stage curls into an echo chamber, where counterpoints that lean to the center are labelled as enemy territory.

This was especially evident in the July debate; when Warren and Sanders kept recycling a certain phrase, they were met with opposition.

John Delaney warned against taking away private health insurance. John Hickenlooper objected to the Green New Deal’s broad promises of government-funded jobs. Jake Tapper asked Bernie how much taxes will rise for his healthcare bill.

The same response kept ringing up: “stop using Republican talking points.”

The intent of this phrase, as I see it, is to paint criticism as illegitimate partisan attacks. It’s defense built from offense––take the hard questions, that many voters are interested in getting direct answers to, and mark it as Republican, Trumpian spam.

This attitude has continued monthly. Of course, it doesn’t ruin the entire debate––most major candidates have their shining moments of clarity––but it confuses the very intent of these debates, which is to give the candidates a chance to explain their policies and disagree, so that we viewers can determine their differences and make the most educated vote we can. What is not needed is a constant, propaganda-esque reminder of our unity against those dreaded Republicans!

At the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Michelle Obama famously said, “When they go low, we go high.” Do not weaken the potential of your vote by thinking only in terms of who you are beating out. Vote for a positive, progressive vision of the future, not simply an anti-Trump candidate.

But everyone––this is a lesson that transcends party lines. I don’t know if politics could be an expression of love, but I like to believe that the heavy focus on partisan differences and identity could be relieved. That politics can be less an expression of electability and more an expression of a concrete stance, a vision.

In short, ShopRite instead of ShopWrong.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam, Opinion

Noah Bergam (V)

In the spring of last year, some friends and I became obsessed with an online game called Diplomacy. In this wonderfully irritating game, each player owns a certain pre-WWI European country, and, move by move, they try to maximize their territory.

Since each player starts out with roughly the same resources, the only way to succeed is to make alliances, to get people to trust you, and, of course, to silently betray that trust at some point to reach the top.

This was perhaps the first time I was introduced to the concept of a zero-sum game––a system where, in order to gain, someone else must lose. I was terrible at it. I didn’t have the confidence to really scare anyone. I couldn’t keep a secret for my life. And worst of all, I couldn’t get anyone to trust me.

The ‘game’ I was most familiar with up to that point was that of school, of direct merit. A system where hard work and quality results are supposed to pay off on an individual basis, and one person’s success doesn’t have to mean another’s failure.

I was especially entrenched in that mindset when my brother went to Pingry. I looked up to his leadership and social abilities, his diplomacy essentially, and realized I could never be like him in that realm––I didn’t have the same sort of outward confidence and social cunning. All I could do was look at his numbers and try my best to one-up them; in my mind, that was the only way for me to prove I wasn’t inferior.

But now that brotherly competition is gone. And I have the leadership I’ve been working toward. And now I’m realizing that, from my current perspective, Pingry’s system of student leadership is not the game of direct merit I thought it was. I wouldn’t go so far to say it’s a bloodbath, zero sum-game, but there’s certainly an element of transaction, and therefore diplomacy, you have to master. Complex transactions of time and energy for club tenure and awards.

It’s really an economy of accolades, where the currency is our effort as students outside the classroom. We involve ourselves in activities and invest our time, of course, to do things we love, but there’s no denying that there’s an incentive to earn a title, a position of leadership that can be translated onto a resumé.

It’s an ugly mindset, but it unfortunately exists. And the ruling principle is merit diplomacy––for the underclassmen, a more merit-oriented rise through application processes and appointments, and for upperclassmen leaders, a need to balance the prerogatives and talents of constituent club members.

That diplomatic end for the student leader is taxing. You have to think in terms of your own defense when people doubt your abilities. You need to make sure people still invest time in what you run. You want respect. Friendship. But sometimes you can’t shake off the guilt of getting that position, because you know the anxious feeling of watching and waiting for that reward.

Now your mistakes are visible. Now you have to know why you have the position you have, and why others should follow you. You need legitimacy to hold on to what you have.

I’m the first junior editor-in-chief of this paper in recent memory. And I know that raises eyebrows to my counterparts who know my brother was editor-in-chief last year. I acknowledge that publicly, because I’m putting the integrity and openness of my job here above my own personal fear of being seen as some privileged sequel. I’m not going to let whispers define my work. I know who I am, and it’s more than just this title. It’s more than a well-spent investment in the economy of accolades. And I’ll prove it.

That’s what the diplomacy side of things teaches you. You come to a watershed moment in high school where you pass the illusion of the merit machine and realize it’s all a matter of communication.

Merit diplomacy can be an ugly and nerve wracking concept; it’s damaging to take it so seriously. It distracts from true passion, and it reinforces the bubble of Pingry life, making us deify our in-school positions and the idea of the accolade rather than the identity of the students themselves.

There are communities and worlds beyond this school. And one might think of Pingry’s economy of accolades as the microcosm of the ‘real world.’ But I think even that gives it too much credit.

It’s practice. It should be a side thought to our passions, not the intense focus of student life. Merit diplomacy is a game––perhaps a high-stakes game––but a game nonetheless.

Sep 17, 2019 | Noah Bergam, Uncategorized

By Noah Bergam ’21

A few times in the past month I’ve brought up in casual conversation that CLIMATE CHANGE IS THE BIGGEST ISSUE FACING AMERICA, outweighing all other problems except maybe healthcare.

I admit, it’s an annoying way to hijack a perfectly good lunch hour: “Way to make me feel bad about this hamburger, Noah!”

I also will contend that it’s a bad habit to publicly blurt out political opinions for no real reason. I try not to, but when it happens, it happens, and it’s usually a respectful experience I can walk away from with new insights.

Specifically, I’ve come to realize that my thoughts about how to address climate change––that we need heavy carbon taxes, unrestricted economic overhaul, and short term economic fallout––are not necessarily right, that my all-caps thoughts aren’t necessary, trump card, scientific fact; they’re opinions, and I tend to lose sight of that.

I think a lot of us do. In a way, it’s selfish to go out and assert that this issue is number one because we understand science, that we need to merge all of our priorities down this road, no questions asked. I’m aware of my privilege––I live in a community that has wealth enough to support cleaner industries and not live off manufacturing jobs.

I still believe climate change is the number one issue facing America. But I’ve begun to realize that treating it as such is not the best solution.

I don’t think that’s hypocritical. My vision for a perfect world doesn’t have to line up with my policy plan for an imperfect world. For example, I might believe abortion is an immoral action, but from a policy standpoint I would be pro-choice, because banning abortion would be a public health disaster; there would just be an illegal abortion system that would end up hurting more than helping.

Similarly, while I may think climate change deserves an immediate Green New Deal, I understand the huge ramifications of pushing an unwilling nation into such a project.

Of course, it’s quite necessary that we have to make America and the rest of the world come to terms with the facts of climate change. Our nation especially needs to stop treating it as a partisan issue. The battle for activism and awareness is crucial no matter what course of action we take.

But until that battle is won, a real Green New Deal is not an economically viable solution.

The only way out is investing in technology and making legitimate progress in geoengineering, carbon capture and storage, environmental engineering of all kinds, and of course, renewable sources. We must optimize solar and wind, clean up and consolidate nuclear energy––in all cases, positively incentivize the shift away from fossil fuels. Until fighting climate change becomes profitable, it will be virtually impossible to enact change to the fossil-fuel-industrial-complex without incredible pushback.

What is not going to fix climate change is words alone.

If history has taught us anything, it’s that technology effects change much faster than words. The Industrial Revolution was easily the most effective and indelible revolution in history. While most human-led rebellions ended up putting power back into the hands of the wealthy and powerful, the Industrial Revolution and the eddies of it that still spin around the world today have actually increased the average standard of living in practically every regard, what with vaccines, birth control, and boosted agricultural productivity.

Of course, history provides us with rife examples of revolutions that have succeeded in their goal, that have successfully changed the status quo in regard to equality under law or self-determination.

But climate change doesn’t stem from prejudice or independence per se, although it is definitely tied to those concepts. To fix climate change, making the average person acknowledge its threat and act accordingly is just the first step: a necessary words-based revolution that we must fight, but a first step nonetheless.

Many activists, and even candidates for president, are chasing a second step that is still a words-based revolution––and that is where we see the issues. This second step, in their eyes, is to regulate industry on an unprecedented level, to force the US economy, and hopefully that of the world as well, to discard short term profits for the long term betterment of the earth. Some spin on the concept of a Green New Deal.

The issue is visible in the phrase itself. Roosevelt’s New Deal was catalyzed by dire circumstances, not scientific consensus of a future issue. Global warming is a slow burn, nothing like the sharp crash of the 1929 world economy. World destruction is foreseeable, but is not something the government wants to necessarily take the jump and address at the moment, while the economy is still going well. Governments and economies have a tendency to act ad hoc, or worse, push the issue to the future, rather than foresee issues and act accordingly. The US government, designed with a conveniently short four-year executive term, has done so with a whole host of issues, ranging from slavery to civil rights to Vietnam.

Why should we have reason to believe that today is any different?

If we do find a solution to climate change before climate change causes massive disaster, we have to find the solution. No matter how much Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion chastise the world’s officials, we can’t rely on such officials to design unrealistic compromises with what little green options they have. They need more to work with. They need something marketable.

That marketable solution, of course, will take government funds in the form of research grants and subsidies; it will take serious, dedicated scientific work. We need to develop the technology that can challenge fossil fuels on a global scale. Because, yes, even if America or Britain or Sweden can forcefully, governmentally realize a green economy, there is certainly no guarantee that developing nations who have yet to reap the full benefits of fossil fuels will follow suit and give up all their potential gains.

When thinking in crisis mode, it is easy to lose sight of just how hard it is to get the rest of the world on the same page as you. The world is abundant with problems. The lunch hour is rife with opinions.

And that lunch hour ends. The world churns on. The Arctic melts. Words certainly matter, but they work slower than we think.

Mar 24, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam, Opinion

By Noah Bergam ’21

Ask almost any Pingry student who Billy McFarland is, and the response is quick: he’s the Fyre Festival guy. The fraudster. The former Pingry student.

For me, that last part has always been an afterthought, a small irony. I heard about it back when the festival came crashing down in 2017, and whenever the name came up it was a fun laugh.

But when I watched the Netflix documentary about the Fyre Festival, something about the whole disaster was brought to life in a disturbing way. Witnessing plans crash in real time, with the livelihoods of so many people put at risk, the amount of time and money and pride put to waste on a fraudulent business model — it all makes you wonder what kind of person it takes to remorselessly allow this to happen.

Sure, he was a person who went to this school. But he’s also a person that a lot of us will now immediately characterize as “crazy” or “malicious.” Someone whose mind just works in a different, broken way that we can’t relate to. Someone who we can frame as the butt of endless SAC memes of the week.

But I believe that this mindset of quick assumptions is deeply flawed, and I don’t say that in defense of McFarland. I think we have to understand him and his intentions in a much more complex way in order to properly learn from his mistakes.

I would argue that Billy McFarland is the product of a greater generational shift, a far-reaching phenomenon that I like to call Fyre. It’s an addiction, an obsession with attention, in which one’s ambitious words and the attention they gather outpace their abilities to make those promises come true. This is what allowed Billy to get investors on his side and to turn his impossible festival into a sellout show — he had an excessive Fyre, a pride in his lies. The people around him mistook that for true, entrepreneurial fire – and were proven utterly wrong.

But this idea applies to much more than just fraudulent tech startups. We all, at some point, have set out on a course of action with faulty ambition and pride, saying things that we can’t fully back up. This Fyre manifests itself everywhere across this very school — in promises to friends, club announcements, resumes, memes of the week, and probably even some Pingry Record articles. And the reason I ask Pingry in specific to look inwards is because, in my experience, we reside in an extremely success-oriented community.

I don’t think that statement would come as a surprise to anyone. Moreover, there is nothing wrong with that; in many ways, it inspires students to put their best foot forward. That being said, this focus on success translates into an even larger focus on ego, on reputation. Whether social or academic, these reputations can be boosted by exaggerations or small lies, which, over time, can add up. Often, especially in an environment as trusting as Pingry, these words can successfully create the desired illusion of wit or success, and thus be fostered further.

Perhaps more often than we as a community are willing to let on, people get away with this, and nobody gets hurt. But when this Fyre becomes an ingrained habit in our everyday lives, bubbles of lies begin to form. These bubbles can burgeon in importance, until at last, the needle of reality catches up, and the hard truth comes crashing down.

Hence, the story of Billy McFarland. A millennial Icarus, whose Fyre was enormously amplified by the distinctly modern power of an Internet Age. We, too, perhaps on a smaller level, are liable to make those mistakes in our Pingry community if we let lies or exaggerations overtake our reputations.

McFarland may be insane or malicious to some degree, but he showcased a Fyre that is present within all of us. We all need to recognize that instead of simply treating his mistakes as jokes. And hopefully, with that recognition, we all can create a school environment that puts out Fyres rather than encourages them.

Jan 19, 2019 | Athletics, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam ’21

The boys’ basketball team is off to a great start this season, having lost only four seniors to graduation. Under the leadership of Captains Nate Hefner (VI), Kyle Aanstoots (VI), and Ray Fluet (V), the team is excited to kick off the new season.

Last year, the team finished with a record of 4-20 and plans to keep working hard this year for continued improvement and success. Head Coach Jason Murdock said that, “Last season was a year of growth and development, and we are looking forward to bouncing back from our 4-20 record. This season will require a collective effort and I’m looking forward to the guys meeting the challenges ahead of them.”

Coach Murdock looks forward to creating an environment where players feel valued, can have fun with the competitive nature of the game, and, of course, enjoy a few victories.

Murdock has been coaching the team since 2007. When asked what his favorite part of

coaching basketball is, he said, “As a former player, the competition. But as a coach, it’s seeing the relationships formed by the team, and players reaching their potential by creating an

environment that is both challenging and rewarding.”

Jan 19, 2019 | Noah Bergam, School News

By Noah Bergam ’21

Once meant as a method to curb nicotine addiction, vaping has become an increasingly widespread practice among American youth. As the number of vaping high school students across the country rises, it has become ever more important for teens, as well as parents, to understand the health risks of the practice.

For all their flavors and attention in the media, vaping devices, also known as e-cigarettes or e-vaporizers, have had their share of controversy among Pingry’s own community in recent years. As such, all of Pingry’s health classes have already made sure to include important information about the relatively new trend in their curricula. However, until now, parents have mostly been left out of the loop. In response, the Health Department put on an informative health and wellness presentation for parents for the first time about the issue on November 28th.

Led by health teacher Mrs. Nancy Romano and Health Department Chair Mrs. Susan Marotto, the presentation was a response to a request from a number of Pingry parents who wanted to know more about the consequences of vaping devices.

“We wanted to run the meeting to tell parents about some of the risks of vaping,” said Mrs. Marotto. “We wanted to give them information about what vaping devices are, some of the dangers involved, and how they can talk to their children about it.”

Real vaping devices were on display for parents throughout the 75-minute presentation. Overall, it was a very informative night for the community.

Jan 19, 2019 | Athletics, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam ’21

The co-ed wrestling team is off to a promising start this winter, hoping to improve upon their performance from last year. Led by Captains Jack Lyons (VI), Zach Dobson (VI), and Brandon Spellman (VI), as well as talented senior wrestlers like Kamal Brown (VI), Holden Shikany (VI), Max Brotman (VI), and Thomas Campbell (VI), the team has a deep lineup dedicated to making the most of their abilities.

“Wrestling features both team and individual competitions, and in past years, we have produced a number of successful individual efforts,” said Head Coach George Sullivan, referring to Frankie Dillon’s ‘17 state qualification two years ago and Spellman’s impressive state tournament last season. “We are poised to put forth several impressive individual achievements once more, but we also have the depth of talent required to be competitive as a team.”

Sophomore varsity wrestler Sean Lyons (IV) commented that, “We look to send a couple of kids to States and to get everyone to improve on the matches that they didn’t win last year. Some of the close calls we are set up to overcome.”

All in all, the wrestling team aims to push past the limits of recent individual achievements to beat the team record for wins and pull off an amazing season.

Nov 22, 2018 | Athletics, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam ’21

The Pingry boys’ soccer team is aiming high this season. With expectations to win the county championship and make a run at the Non-Public “A” title, the team has maintained an impressive record so far.

Captain Drew Beckmen (VI) recognizes that “alhough we lost our goalkeeper and two all-county defenders to graduation, we have an extremely talented junior class and strong senior leadership leading the way this year. Hopefully, we can combine our strong defense and dynamic attack to be one of the strongest teams in the state.”

The team looks promising, but the hardest is yet to come. Hunterdon Central, a big Group 4 school, and Peddie, which Pingry has not beaten in two years, will provide some serious competition in coming weeks. Recently, the boys defeated Staten Island Academy with a score of 6-0 during Homecoming, on the 90th anniversary of the program’s inception.

Beckmen added that in regards to the Non-Public “A” championships, “We have come up short to Delbarton two years in a row in States, so we are determined to beat them this year. Though Non-Public “A” features the best soccer talent in the state, including the boys attending Seton Hall Prep, Christian Brothers Academy, and Delbarton, we are confident that we can compete with these teams. Hopefully, our good play will continue, and we can continue to show the state that we are a team to be reckoned with.”