Mar 25, 2018 | Editorial, Opinion

By Rachel Chen ’18

When I heard about the tragedy at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, my first reaction was not to have one. “17 dead, 14 injured…” the car radio droned, and I remember thinking, oh. Another one. And I promptly forgot it.

I strive to be compassionate, but after years of hearing about mass shootings every few months, the concept of a mass shooting has lost its tragedy to me. It has become too regular an occurrence for me to summon up the same intensity of grief and despair that it once did. So on Monday afternoon, during an unseasonably warm fire drill, I forced myself to feel the visceral fear of those students under attack in Florida. For one searing second, I tried to imagine what might occur if an active shooter were on campus.

Would I dodge behind cars? Would I run fast enough to reach the BAC? Would I scream as my classmates were cut down, or would shock prevent me from registering it?

Now and in the moment, I shudder. My heart pounds in my ears. 17 dead in a high school of 3000 broke the Parkland community; 17 dead in our entire school of just 1000 would shatter us.

Something needs to change. But why hasn’t it already?

Everyone who passed middle school social studies knows that the Second Amendment guarantees the “right to bear arms,” an important provision in the Revolutionary era for establishing democracy in the face of tyranny and military

abuse. Since those days of muskets and bayonets, the Second Amendment has become a symbol of ultimate freedom—perhaps even more so than freedom of religion, speech, or press.

While other rights have served the same purposes throughout time and thus become established as simple, non-negotiable rights, the right to bear arms has nearly lost its original purpose

as guns become more developed and dangerous. Less thanphysically defending the republic against oppressive government military abuses, it has now evolved into taking an ideological stand for freedom—to the point where owning a gun is a deliberate exercise of that freedom, and the gun itself is used only for recreation.

So the symbolic power of gun ownership drives gun advocates and the National Rifle Association (NRA) to block any legislation proposed to curb our near unfettered access to military grade weapons. Instead, the national conversation

is redirected toward improving the mental health system to prevent the severely mentally ill from obtaining weapons and arming teachers to defend students.

But would these solutions be effective? I doubt it.

In my nightmarish reimagination of our Monday afternoon fire drill, who would be behind the trigger? I may not know any severely sociopathic, mentally volatile aspiring murderers, but I can think of many socially isolated, frustrated, angry teenagers who think they deserve better. Committing every adolescent who fits that profile to a mental institution and a lifetime of mental health stigma would be a greater offense to

constitutional freedom than any gun control restrictions could be.

And who would defend us? Should Dean Ross bring a weapon to Morning Meeting, just in case Should Dean Cottingham carry her pistol from her office to English class in the same bag as her laptop and glasses case? Would I feel any more safe surrounded by teachers with guns who have no experience or desire to wield them?

The image is absurd. Surreal. And for me, the answer is no—no to armed teachers, and no to an “improved” mental health system that confuses adolescent rage and clinical psychosis and treats both the same.

Thankfully, students are stepping up. The survivors of Marjory Stoneman Douglas are speaking out, arranging marches and protests, and challenging their representatives to take a

stand. The sorrow that ought to paralyze them is driving them to greater action, and I am grateful for their leadership in this fight for our lives and futures.

And yet somehow, their suffering is not enough. In the eyes of some prominent national leaders, our loss does not make us qualified to speak—it disqualifies us, because we are too young. Too blinded by emotion. Our tiny, undeveloped

prefrontal cortexes are too easily manipulated and influenced by the freedom-hating left agenda.

Somehow, it is the people furthest away from the situationwho are qualified to speak. It is those who are calm because they are remote, who are unafraid because they are unaffected. It is those who are “rational” and “experienced” because they will never have to picture themselves hiding underneath desks and behind cars from classmates wielding AR-15s.

What would the victims of Parkland say to that?What would the founding fathers think? Maybe I don’t know enough. I don’t understand the intricacies of politics, the checks and balances, the hard-earned compromises that got us to today. I definitely don’t understand the appeal of and attachment to assault weapons that so many Americans feel so passionately. But here’s what I do know: I am 17. I go to a school—like

Sandy Hook, like Columbine, like Marjory Stoneman Douglas High—and I am afraid. I may not have all the answers, but I think I deserve a chance in finding them.

Mar 25, 2018 | Opinion

By Maddie Parrish (VI)

“Everything seemed so easy. No way we would get caught.”

This is a quote from the notebook of Eric Harris, one of the two perpetrators of the Columbine High School shooting in 1999 that killed 13 people. Since then, journalists have attempted to pinpoint some of the motives of the boys: Eric was, according to psychiatrists, a psychopath, Dylan Klebold was depressed, and together they wanted to “wipe out as much humanity as possible” (a quote from Eric). When considering what causes any killer to pull the trigger, mental health is often a critical issue. Nikolas Cruz, responsible for the recent Parkland shooting, had previously been diagnosed with depression. But for many mass shootings, there is another common characteristic among the perpetrators: they look to previous incidents for inspiration.

Since Columbine, there have been 208 school shootings in the US, and an ABC News investigation pointed to 53 attempted or successful school shootings in which the killer explicitly cited Columbine as an inspiration. How could a single act of violence turn into a cycle across America? The answer to this question, although complex, lies partly in the quote from Eric’s notebook.

According to a 2007 survey, the US owns an estimated 48% of the world’s 650 million civilian-owned firearms. We own more guns per capita than residents of any other country. The history of the Second Amendment and the prevalence of guns in the United States means that measures taken in other countries like Australia to essentially ban gun ownership would not work the same way in the US, but also that US citizens are more inclined to turn to guns as their mode of violence. This is made possible by insufficient state regulation of private gun sales. After all, everything was so easy for Eric; even though he had previously been arrested and local law enforcement had seen his website on which he wrote about making pipe bombs, he was able to buy a TEC-9 (a semi-automatic pistol) and three other guns at a private gun show where the seller was not legally required to perform a background check.

Federal law only requires background checks for gun sales by federally licensed firearm dealers, and states have their own laws for gun regulation. Currently, only 12 states (including NJ) and DC require background checks for all privately sold firearms, and six more states require background checks for privately sold handguns only. The statistics are alarming: a 2017 study estimated that 42% of US gun owners acquired their most recent firearm without a background check, and a survey in 13 states of state prison inmates who were convicted of gun offenses found that only 13% obtained the gun from a gun store where background checks are required. So, why is it that 32 states don’t require background checks at all for private gun sales?

The arguments against background checks for private sales include the possibility that innocent citizens might be denied guns because of flaws in the background check system and the claim that regulations would be too difficult to enforce. However, these are justifiable risks of common sense regulations as the federal government works to improve the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. After the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas, it is clear that the net benefits of preventing firearms from falling into the wrong hands outweigh any potential negative consequences.

Additionally, if state and local law enforcement struggle to enforce these regulations at first, perhaps private companies could help out by providing background checks for private gun sales. Walmart is the largest seller of firearms in the United States and performs its background checks through NICS. Being the largest private employer in 22 states, Walmart has tremendous influence and already requires employees who sell firearms to get a background check even when state regulation doesn’t. Companies like Walmart could act as a sort of middle-man, providing more convenient background checks for local private sellers to enforce state regulations.

In the meantime, Pingry students and high schoolers across America who are both angry and fearful should not and are not remaining silent on the issue. Students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School are sparking an incredibly powerful movement on a crucial issue, and as it gains momentum across the country, listening to students’ requests and implementing common sense firearm regulations is the least state legislatures can do.

Mar 25, 2018 | Editorial, Opinion

By Megan Pan ’18

In the past few weeks, we’ve had the chance to hear some excellent speeches about parenting. At the LeBow Competition, Jonathan Chen (V) talked about his parents’ “endless love and endless support” and urged us to “thank those who support you,” while at last week’s Morning Meeting, Mr. Keating shared stories about his own parents and encouraged us to “pay attention to how your parents are raising you.” Even Mr. Andrew Onimus, in his presentation at the Carver Lecture, emphasized the support he received from his parents in his struggle with mental illness. Spurred by their example, I’d like to take the time now to pen atribute to my own parents

Since before even I was born, both of my parents commuted every day to work in the city. Sometimes if I woke up early enough, I could hear from down the hall the rustling sounds of my parents getting ready in the morning.

Nestled underneath the warm covers, I listened through a semi-conscious, sleep-clouded haze to the sound of water striking tile in the shower like keys of a typewriter, the crisp click of my mother’s high heels and the swift zip of a jacket, and finally the distant roar of the car ignition growing ever fainter as my parents drove off into the dawn. As I heard but never saw my parents in the mornings, these sounds were the only confirmation that my parents did in fact exist prior to six in the evening and did not simply materialize every night out of thin air, complete with work-weary faces and the perfume of the commuter train.

Nevertheless, it was anything but an unhappy life. The many grown-ups who watched over me during the day treated me kindly, and there was no shortage of love on the part of my parents either. But even if I can say that now, looking back in retrospect, I can’t deny that there were times during my childhood life when I simply felt that something was different. Not missing, necessarily, not wrong either—just different. In the eyes of a young child learning to observe the world around her, the small inconsistencies between other families and hers must have imprinted themselves in her mind; a quick kiss planted on a reluctant cheek in the morning carpool line, a lunch box complete with sandwich and sticky note lovingly packed, a pair of arms outstretched in greeting, waiting at the door—she must have circled them in her memory as if they were objects in a game of spot the difference.

My parents’ love felt like the light of the sun—brilliant, warm, and vividly palpable, but ultimately exer- cised through the physical barrier of distance. However, I never felt any resentment towards them, even as a child. In fact, it is as a result of their absence in my childhood that I believe I am able to better appreciate them now. As opposed to being something that is taken for granted, their presence is something that is alive and dynamic, like a flower wriggling its roots through the dirt or a fire breathing smoke through its embers. Throughout the years of my development, I have grown up and become increasingly independent. One by one, the adults who had watched over and cared for me as a child have let go of my hand, and I have since stepped forward to join them in line as a fledgling adult myself. The responsibility for my own well-being has now fallen squarely on my shoulders with no one else to lead me.

That is, with the exception of my parents. Even now when I’m expected to be able to walk on my own, my parents still remain by my side and serve as a source of guidance and support. But unlike the child for whom the surrogate love of others eclipsed the solitude she felt, I have since learned to become receptive to my parents’ love in every form that it takes.

In parting, I would like to urge members of the Pingry community—adults as well as adolescents- to remember their parents and to be forgiving of them. If there is anything in my perception of my parents that has changed from childhood, it is that I have learned that they are fallibly, beautifully human, subject to the same emotions, desires, and fears as we all are. The true strength of my parents’ love manifests itself in its endurance. Throughout all this time, it has never wavered or faltered—instead growing to overcome any barrier in its way, like vines of ivy winding their way upward, ever upward in search of sunlight.

Mar 25, 2018 | Opinion

By Felicia Ho (V)

“At 17 years old, he’s won it — the first gold medal for the United States at the 2018 Winter Olympics.” “She’s a golden girl! What a force to be reckoned with!” As the Winter Olympic Games opened in Pyeongchang, South Korea on February 9, two breakout snowboarding stars, Red Gerard and Chloe Kim, shone on the glittering half pipe. Immediately they became Internet sensations and lit up headlines on newspapers around the world; they had made their mark, one for the ages, in this year’s Olympics. Although these two young rising stars are beaming signs of hope in the 2022 Olympics, it is important to remember that the Olympics also celebrates stories of veterans.

There are several five-time Olympians competing in the Games this year, including Aliona Savchenko, a German pairs figure skater, and Kelly Clark, an American snowboarder. Lindsey Vonn, an American skier, is competing in her fourth Olympics, and Mirai Nagasu, an American figure skater, is in her second Olympics. These veterans all have their own outstanding stories of getting back up when they’ve been wiped out, of taking up the courage to compete again after failing to qualify for the Olympics in previous years. After all their sweat and tears, they’ve pushed through to make it to the podium. And even if they don’t win, they continue to work even harder than before, inspiring athletes like Red and Chloe.

“Today I wrote history… This is what counts,” Savchenko said after she finished her record-breaking gold medal free skate pairs program with her skating partner, Bruno Massot. Savchenko had been a Bronze medalist in both the Vancouver 2010 and Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, but never before had she clinched a cold, hard, golden medal in her hands. Although her age posed a challenge in continuing a physically demanding career, she fought on, and the results have paid off, as she is now the oldest woman to win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating.

Similarly, Kelly Clark at 34 years old defies her age in snowboarding. Although her last Olympic gold medal in half pipe snowboarding was over a decade ago, at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, Clark continued to fight for gold at this year’s Olympics. Although unsuccessful in her attempts and capturing 4th place instead, Clark has not regretted a single moment of the work she has put herself through. Instead, she looks to inspire the next generation, explaining, “Your dreams are too small if they only include you.” Kim acknowledged Clark’s mission by presenting Clark with the Order of Ikkos Medal because “she just took me under her wing,” in reference to meeting Clark when Kim was only eight years old.

This close relationship between Clark and Kim embodies the true meaning of the Olympics: to inspire and encourage the future to challenge their limits, break records, and above all, create a lasting impact that will change history forever. Whether it be figure skating, performing in a show, or even finishing an exam with the flourish of a pen, we are built to follow our dreams, no matter how big or small they are. Once we achieve those dreams, we become an example to the people around us who cheer us on every day.

As the Olympic athletes representing Team USA are in Pyeongchang to be the #BestOfUs, we students are in Basking Ridge and Short Hills to be the #BestOfPingry. Although the competition is strong and can be overwhelming at times, we must learn to overcome that feeling and “skate” to our own songs. Our own coaches—our parents, counselors, and teachers—are watching in the bleachers, advising us every step of the way even as we fall. At times we shine in the spotlight alone, and at other times we share the spotlight, hand in hand.

For each day that we walk through those double doors, we step onto the ice a little more confidently as we are ready to amaze this big wide world.

Mar 25, 2018 | Opinion

By Ketaki Tavan (V)

The first time I was ever exposed to the concept of affinity groups was during my freshman year at Pingry. These groups were presented as “safe spaces for students to learn more about their various identities and to discuss their questions, comments, and concerns with other students who share that same identity.” My initial reaction was confusion–I couldn’t wrap my head around why we’d want to create spaces that physically separated students of different identities when the ultimate goal of our community should be inclusion and acceptance.

After this initial introduction, I hadn’t thoroughly revisited the concept of affinity groups until this year, when I was presented with the opportunity to lead the South Asian Affinity Group. With this opportunity came the task of thoughtfully considering the purposes and goals of affinity groups. Through affinity group leader training, I became more familiar with these objectives.

It became clear to me that affinity groups are a space to process and explore your identity with people who share it. I find this especially valuable as a minority in a community, country, and time. Even though I don’t necessarily feel marginalized or targeted on a regular basis, I also don’t feel like my environment is conducive to a complete freedom to embrace and grapple with my South Asian heritage.

Although I’ve found the South Asian Affinity Group to be an invaluable space where I can connect with those who can relate to the challenges I face and questions I have regarding my identity, I do understand those who believe that these spaces are divisive.

In discussing the potentially divisive nature of affinity groups, I think it’s important for people to first and foremost recognize that these groups aren’t meant to end where they start. Rather than creating identifier-specific groups that are separate but equal, affinity groups should and do serve as stimuli for conversations within cultural groups as to how each of us can effectively support productive cross-cultural dialogues as well as consider how we fit into the bigger and more diverse communities of our school and the outside world. However, this purpose is a fragile one that may not always be fully achieved.

It’s easy for affinity groups to become the only spaces where honest, identifier-related discussions are held as members return to the larger community and forget about them. This results in limited change; affinity groups are a space for our smaller groups to make progress, but Pingry lacks a structure that allows for inter-group work between each of their attendees to take place.

Ideally, this structure would be the everyday interactions of our community in its natural state, and oftentimes I find that it is. I’ve had plenty of productive and thought-provoking conversations with students with cultural identifiers different to mine that were inspired by conversations we had in our respective affinity groups. But I do think it’s potentially naïve to assume it unnecessary to have a bigger processing space where the progress made in smaller affinity groups can clearly be seen.

I also think that this lack of an inter-affinity group structure contributes to people’s fears that affinity groups are divisive. The anxiety and suspicion that can arise from a lack of insight into the work done in other affinity groups has nothing to calm it, resulting in decreased buy-in toward them in our community. Not everyone trusts that the larger processing space necessary as a follow-up to affinity groups will take form naturally in the outside world. Therefore, it would be beneficial for both those who doubt affinity groups’ effectiveness and for the realization of the ultimate goal of affinity groups to create this space at Pingry. There are many forms that this space could take; the two open forums we had this year where all students could attend were great examples.

I do believe that affinity groups are a step in the right direction on the path to equality and inclusion. I’ve found my participation in them to be an important part of my connection to my South Asian identity. That being said, I do believe there’s more to be done before affinity groups can fully accomplish their ultimate goal.

Dec 24, 2017 | Opinion

By Brooke Murphy ’18

As many people have seen by now, a new “Participation Policy” has been put in place. The policy, which was emailed to parents around November 26, states that students must participate in activities that they excel in throughout their time as a student in the Upper School.

Soon after parents received this email, there was backlash in student group chats and on social media. Students questioned why and how the school would be able to require such a thing. Specifically, how could the school require a student to take his or her time after school to participate in one of the school’s athletic teams?

Fundamentally, I agree that any student who does have a talent in a certain area should want to contribute that talent to his or her school community. But is it fair of the school to threaten dismissal of a student if he or she doesn’t do so? As a player on one of school’s tennis teams, I have seen the type of situation where players who would have been members of the varsity team do not play for Pingry.

The fear of loss and of not being the top player has driven members away from the bigger picture of team success. Of course, I do not know students’ reasons for not joining or continuing their time on the tennis team, but this policy has called me to question whether it was fair of these players to quit the school team. Is it fair that qualified athletes don’t contribute their skills to the community?

Not only as a member of the Pingry tennis team, but also as a member of a much larger tennis community, I have seen this type of behavior before. I have seen many girls across the state of New Jersey who don’t play for their high school teams because they believe that playing on a team far below their skill level will hinder their careers, that playing on a high school tennis team is not worth their time, or, in many cases, that playing on the team will lead to more losses, a result they are afraid of. An important question is raised by the situation: On what grounds can these girls’ schools require players to play for their teams?

Pingry has grounded their policy in the Honor Code. The Honor Code states that students should work for the “common good rather than solely for personal advantage.” After quoting this section of the text, the policy continues: “Accordingly, it is Pingry’s expectation that students will participate in ways that advantage the community.”

However, as one reads further, it can be noted that this “expectation” is actually a requirement – one that, if not fulfilled, might result in the denial of enrollment for the following school year. Is it more selfish for the school to require such players to dedicate such a large portion of their time to its programs or for the students to choose not to share their talents through the school’s programs?

As a highly ranked and highly dedicated tennis player, I have always felt compelled to play for my school’s tennis team and help the team advance to every championship possible. For a tennis team, the loss of even one player can make a huge impact. However, it is within my own morals that I feel as though I should play to help a larger focus than myself, and it is my choice to express this sense of obligation through Pingry’s teams and not elsewhere. Others may interpret their own morals through different actions, maybe by participating in a community outside of the school.

I believe that every student should be an active member of whatever he or she can in the school community, but it should be within his or her own moral standards. It shouldn’t have to be forced upon these students by regulations or threats of expulsion. With this, I would urge not only for students to dive into the rich programs Pingry has to offer, but also for the school’s administration to appreciate the students who already want to benefit the community and not just those students who are deemed more talented and valuable to the school.

Dec 24, 2017 | Opinion

By Felicia Ho (V)

Shrill, piercing, and unbelievably scratchy. The first time I heard a violin, I couldn’t believe my ears. Yet, there I was at my local music shop, picking out my first violin as a fourth grader. Hundreds of violins lined the walls, waiting to be brought to life with a single bow stroke. A select few were lined against the back wall; they were the chosen ones that had been treasured for centuries on end by the old and the young. As I grasped the neck of a dark brown, German-made violin and picked up a bow, I was determined to let its voice ring to the world for the first time.

When I was in the Lower School, coming to the Winter Festival at the Upper School was always the highlight of my year. I couldn’t wait to sink into those big, comfy red and blue chairs in Hauser Auditorium as Mr. Berdos waved his baton to begin the concert. My gaze always fell on the concertmaster, who was a quiet yet important leader of the entire orchestra and always seemed perfectly in sync with the conductor.

Years later, I’m no longer ensconced in the comfort of the red chair. Instead, I am sitting in a hard, black metal chair as a part of the Upper School string orchestra. As the conductor’s baton waves overhead, I look at the same piece I have played for four years and try to make sense of the black lines that flood the page. Around me on the stands, heads are bobbing up and down, and there are wide gaps in the bleachers that had once been filled with eager faces and cheery smiles. As I look out to the audience, rows and rows of seats are empty. Those performing glance down at flashing phone screens, impatiently tapping their feet, their minds on school and work.

What has happened to the power of music? Why is it no longer bringing people together the way it used to?

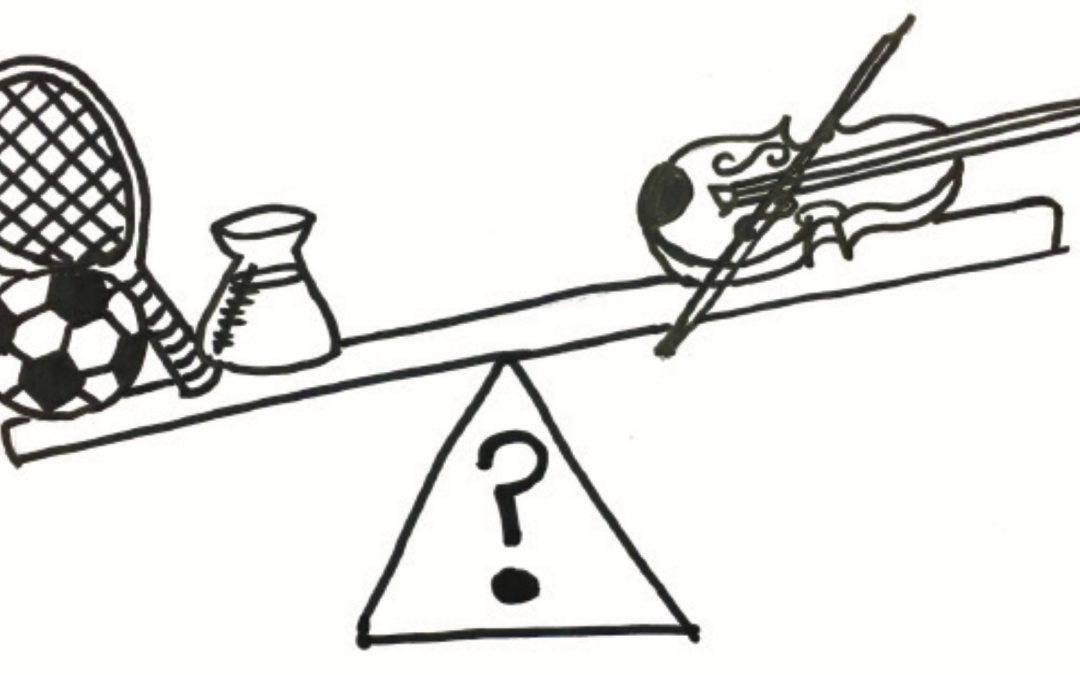

The answer may lie in the recent budget cuts on national arts programs, a result of the increased emphasis being placed on STEM and athletics programs. In March, President Trump announced that “… the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities would be eliminated entirely…” (NPR). Historically viewed as an integral part of education, the arts have begun to fade, largely due to their perceived “uselessness” in an era of progressive technology.

But why was music so important in the first place? Was it not to connect the world, breaking all barriers, be they linguistic or geographical? Music is the universal language, and directing funds and support away from this important subject is damaging to current and future generations. Now more than ever, we need music to connect us in these divisive and stressful times. Without sufficient emphasis on music programs, we cannot compose this bridge.

Fortunately, Pingry is heading in the right direction. Although it has spent most of its budget and time on STEM and athletic programs in the past, the school is beginning to improve the arts programs. Just this year, the newly formed percussion ensemble blew me away at the Winter Festival, and the newly appointed Arts Ambassadors have paved the way for Pingry arts programs in gaining more recognition from fellow classmates. In addition, Hostetter on the Five performances are great venues for student musicians to share their talent and music with the community.

Making a violin sing is not an easy job, as I’ve learned in the past seven years. Every day I’m faced with a new challenge, whether it be the difficult rhythm, technique, or structure of a piece. But I’ve learned to push forward, and the results can be rewarding. If everyone in the community can join together in a harmony by attending and supporting their peers at school concerts, we can truly make our hearts sing together.

Dec 24, 2017 | Opinion

By Darlene Fung (V)

I am a swimmer, and being a swimmer means having a notoriously large appetite. We high school swimmers might not be inhaling Michael Phelps’s famous 12,000-calorie diet, but we certainly do consume more than the 2,000 calories an average American eats in a day. That being said, over one third of my daily food intake comes from Pingry’s cafeteria, and if I’m being totally honest, I love it.

While some may not share this sentiment, I look forward to lunch at school every day. I came to Pingry as a freshman, and I vividly remember my buddy day. I sat through a health class, a chemistry class, and a geometry class. The classes were all great, but I have to say, lunch was my favorite part of that day. I was floored by the swarm of students walking around with a wide variety of well-portioned meals that were vibrant in color, served on real plates, and eaten with real silverware. There was chicken, and rice, and pasta, and grilled cheese, and salad, and a panini station, and peanut butter and jelly—the options seemed endless!

I’ve been to other schools’ cafeterias where students are served a few chicken nuggets, one scoop of mashed potatoes that are made from powder, and some canned fruit that consists of a couple of beige cubes floating in syrup. On other days, students get a boiled hot dog set on a slice of white bread, a scoop of brown bean paste, and some soggy, gray collard greens that nobody but the bravest kid would eat. Food is served on styrofoam trays that are smaller than the average Pingry student’s laptop, and that’s that.

The difference between these schools’ lunches and Pingry’s lunch is night and day, and come freshman year, I was exceedingly satisfied with my dining experience at Pingry. I was so grateful to have a variety of healthy options to choose from as well as the chance to grab a piece of fruit to snack on throughout the day.

As my freshman year went on, I also became increasingly appreciative of the care taken to make our dining experience the best it can be. The kitchen staff puts an incredible amount of effort into serving hundreds of hungry, growing students a variety of over six different meal options daily. Even when we are not at school for lunch, whether for a game or a field trip, we are still served food thanks to the extra time put in to make brown bag lunches on top of regular in-school lunches.

In addition to the effort the kitchen staff puts into all the nutritious meals they prepare for us, they go above and beyond to tend to the small details regarding how we are served as well. Every day, just like my first day of freshman year, I am greeted with a warm smile and a “Hi, how may I help you?” before I am served a neatly portioned plate of food complete with an extra ladle of sauce, a sprinkling of green onions, or even an edible flower.

It is the special care the kitchen staff put into the deliciously prepared lunches we enjoy five days a week that makes our dining experience all the more meaningful. So the next time you are in line waiting for lunch, don’t forget to express your gratitude to the kitchen staff. And if you find something that doesn’t particularly suit your taste, think about how lucky we are compared to the students in some other schools. Just as we already appreciate the amazing choices we have in classes, sports, art, and beyond, we should show our appreciation for the great choices we have in our lunches as well.

Dec 24, 2017 | Opinion

By Alexis Elliot ’18

“Ok, now can you describe yourself in 30 seconds or less?” During my college interview, I shifted in my seat as I tried to come up with an answer. Not wanting to seem unprepared but also worried to speak without gathering my thoughts, I asked my interviewer to give me a minute to think. As I left the interview, I couldn’t stop thinking about how in all of my life, I’ve never been asked to shrink myself down to 30 seconds. Even as a teen entrepreneur who pitched to Warren Buffet, I had 60 seconds to present a business idea. How much more would a person with an entire life story get?”

The experience I had during my college interview made me wonder if the college application process gives people enough room to explain who they really are. As I work on many of my college supplements, although I’m happy to get many of them out of the way, I sometimes worry that I didn’t mention many of my activities or certain life experiences that I really valued. Focusing on events that occurred only during high school — as the process requires — isn’t enough to capture the range of my life.

Furthermore, my fellow classmates seem to agree with me. In a voluntary survey conducted in the Class of 2018, 68% responded that they feel the college application process does not give applicants enough room to express who they are.

As a result, it’s easy for students to get stuck trying to balance moderation and simplicity. Yes, colleges value students who show a wide variety of achievements and interests, but they also value students who thrive in a few select areas. This paradox creates the challenge of trying to display all of one’s achievements while trying not to seem all over the place.

Further, I’ve found myself having to pick and choose which aspects of my life I want to demonstrate as ones that I value the most. Of course words on an application can’t encompass an entire person’s life experiences or values. But, I often find it hard to choose which values I want to incorporate. Do I talk about my experience playing soccer with an all-boys team in Ghana? Or should I talk about something more academic like participating in a coding camp for seven weeks?

Interestingly, in Peer Leadership, we were faced with this same task. We were instructed to write words or phrases that make up our identity. We then had to put them on a wheel with the things we value most taking up more space. Many of us found it difficult to prioritize some things over others. Shrinking ourselves down into categories felt impossible.

For argument’s sake, the college application process has many positives. Even though we don’t have much space to focus on many aspects of our lives, the essays are required to be short because so many millions apply. Another point to consider is that recommendation letters and interviews help account for the more personal side of the process.

Even so, the process still allows much of what makes up an applicant to get lost.

While the college process won’t drastically change anytime soon, that shouldn’t discourage us. Sometimes saying less is more. American photographer and environmentalist Ansel Adams wrote, “When words become unclear, I shall focus on photographs. When images become inadequate, I shall be content with silence.”

Even though it’s easy for us to go crazy trying to explain ourselves in our applications, we should sometimes opt to just leave things out when it becomes too much. Don’t be afraid to keep an essay or explanation simple. Get your point across, but don’t feel burdened to hit every detail or every experience. Yes, there is the pressure to prove yourself to a college by explaining everything. But there is also beauty in the mysteriousness of having unfinished chapters in the story of your life.

Dec 24, 2017 | Editorial, Opinion

By Megan Pan ’18

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Ever since I was young, I’ve had a strong sense of attachment. My mother told me that when I lost my first tooth, I cried over the loss of a part of me that had been with me for seven years. As I grew older, this sense of attachment developed into a fear of losing hold of the past. While the eponymous hero of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby attempted to recreate the past in the present, I preferred instead to hold on to what remained.

Tangible objects served as portals to the intangible; I kept notebooks from elementary school, saved old voicemails on my phone, and held on to even the most trivial of mementos, like gum wrappers, in order to have an extant link to the people, places, and experiences of my memories. In my mind, preserving my memories of the past in the present validated their having happened, and to lose a piece of my past in the present was to lose the past itself.

In March of 2015, my grandmother passed away. She was the cornerstone of my childhood, practically raising me as my parents worked in the city. My grandmother played a part in all of my happiest memories: teaching me how to ride a bike, driving me back and forth from school, telling me stories before I went to sleep. Upon her death, I lost a beloved family member who was as precious to me as my own life, and the world with her in it that I had known for all my life crumbled away.

I was living in a postmortem world that I never imagined could have existed, and I was unable to find any way of fully bridging the gap back into the world of the past. I had photographs, of course, and clothes she had worn, journals she had written, gifts she had given me—but none of it was enough. Like Harry Potter’s resurrection stone, they managed to conjure the image of my grandmother, but they could not bring her back, nor could they represent the entirety of the love and warmth that I missed.

It was my grandmother’s death that led me to reconsider my obsession with the past. Up until that point, I had lived my life with a retrospective focus, with a preference for the preservation of old. However, during my period of mourning, I realized that my grandmother would not have wanted me to dwell on her death and to forget to live. Everything she had done for me while she was alive was in service of my future, and to disregard that was to dishonor her memory. My grandmother taught me that I must embrace living in the present, trusting that what really mattered from the past would stay with me.

In about two weeks, I’ll be turning eighteen. What a strange thing—the inevitable passage of time! Though my heart feels entirely like that of a child, its vessel has managed to outgrow itself. To be perfectly honest, I never imagined that I would live to see the day I turned eighteen. I don’t mean this in a morbid sense—it’s just that, throughout all these years, the idea of adulthood always seemed so far away, a fantastic mirage somewhere in the distance, beyond the boundary of where I could ever reach. But come January first, I’ll have crossed a threshold, and the door on my childhood years will be gently shut.

However, this isn’t to say that my connection with the past will be completely lost. Though her physical form is now a relic of the past, my grandmother’s spirit has remained with me in the person I am today whom she has helped to shape, and I trust that she will remain with me still in the person I am becoming. Each moment I have lived of life up to this point will play a similar role, molding the clay of my character—hopefully into someone who is kinder, stronger, braver, wiser—as I look forward into the future.

There will always be a part of us that will never completely relinquish its fondness for the past. Nostalgia is a powerful force, so much so that it was once considered an illness afflicting certain groups of people. James Gatz was forever tethered by the remembrance of the past, unable to ever move forward toward the future. However, the plight of Gatsby does not have to be the fate to which we are all condemned.

Instead, the past can serve as the wind in our sails, pushing us past the current as we venture out onto the open sea.