The Light Behind the Dress

By Brynn Weisholtz (VI)

As the sun rises each morning, I wake to see the light peeking through the shades in my bedroom window. In front of that window hangs a gown, my senior prom gown, draped from a hanger with nowhere to go. April 22nd was supposed to be the night of my senior prom, a night that my friends and I have looked forward to since walking through the clocktower doors many years ago. I find myself in a state of limbo, walking from floor to floor and room to room all within the walls of my home. I silently wonder, how can my senior year be slipping away this quickly? Is this really happening? What can I do to turn the shadows of the moment into light for what will ultimately be?

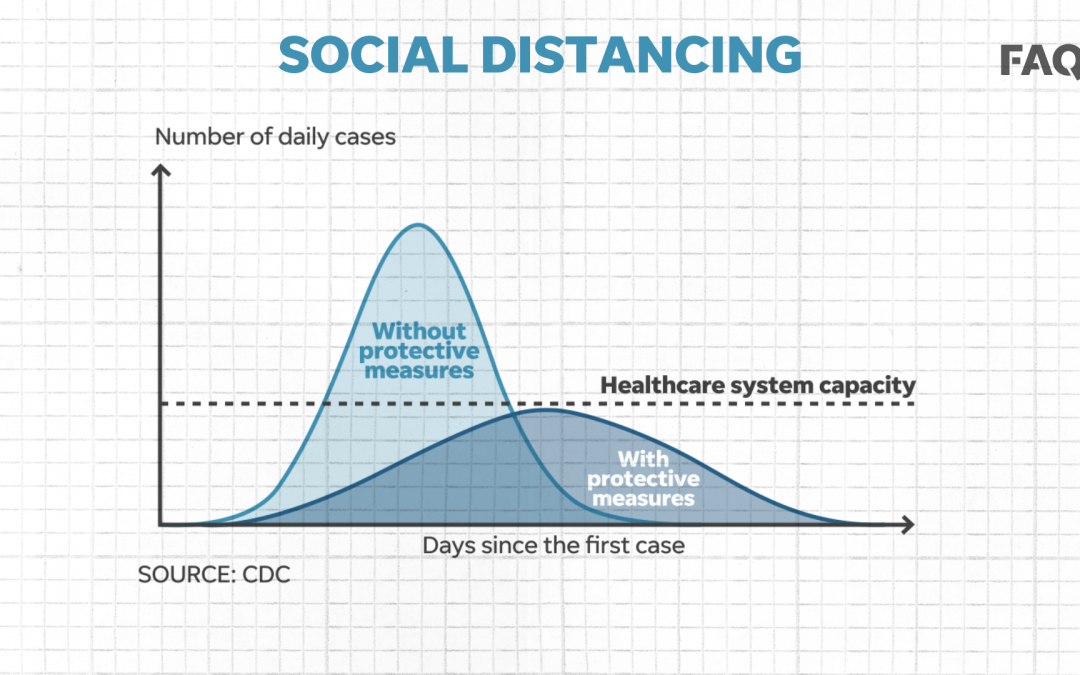

As events started to get cancelled, part of me could only focus on the negatives of this tumultuous turn of events: no prom, no fashion show, no senior prank day, and possibly no graduation. The suddenly unnecessary prom dress casts a shadow on my outlook for the rest of my senior year and beyond. Towns that once were bustling with open businesses and families walking the streets now look more like ghost towns as masked people stop their cars for curbside pick up from their favorite local restaurants. How is life supposed to return to normal? Will we ever shake hands and talk to strangers on the street again? Will our town centers thrive once more?

As quarantine continued and classes began, I developed a morning routine, returning some normalcy to my day. I wake up, brush my teeth, put in contacts, and then start my commute: walk down the stairs, take a sharp right and then a quick left, and I have arrived at my destination, my classroom. While my classes don’t have the same level of energy virtually as they did when on campus, I know students and teachers alike are giving their all to remain upbeat and engaged. We hold on to what we can in the midst of what appears to be life spiralling out of control, and when the day ends I return to my room to see light coming through my prom dress in my window.

The shadow of my prom gown is a subtle reminder of the darkness we all feel as a community, born from the uncertainty and loss of the familiar and the known, the expected and longed for, the mundane and extraordinary––but I choose to see the light. I choose to focus on the moments when the sunlight escapes and shines through the shadows, illuminating the silhouette of my dress and reminding me to embrace the here and now, to be thankful for those around me, and, above all, to be hopeful for the joys of life that will emerge in the days and months ahead.

While the world is at a socially-distanced standstill, the ways the public has been able to shift into this new norm is nothing short of remarkable. In what felt like a blink of an eye, we’ve connected via our computers, reached out to old friends, checked in on our grandparents, and found appreciation for what was. We have embraced the unexpected family time that was once thought as long gone. My brother, another graduating senior, now lives at home for the first time in four years, bringing back game nights, family dinners, movie nights, wiffleball games in the backyard, and walks through our neighborhood.

Though I miss seeing my friends, having passing conversations in the hallways with teachers, and occupying Mr. Ross’ office, we as a community are making the best of everything. I continue to be inspired by those around me and optimistic for our collective futures. In light of this, I took down my prom dress from the window and let all the light shine through.