Apr 17, 2020 | COVID-19, Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

The Pingry tuition for the 2019-20 school year was $42,493. Lunch cost $1,378. Those are significant numbers in my life, numbers that, for over six years, have hovered over my head, acting as a reminder of what doesn’t go to my younger siblings each year.

Those numbers are especially relevant in the era of remote learning. Assuming the very likely scenario that the rest of the school year is remote, it appears students are on track to lose out on both tangible and intangible aspects of an expensive educational experience. This problem, of course, isn’t unique to Pingry. Many universities have issued refunds on room and board and meal plans in the wake of this change. I believe Pingry ought to follow suit and prorate our SAGE Dining meal plans––and while it is unlikely that we could receive a partial refund on the less quantifiable intangibles that we lost this year, it’s a conversation worth opening up … especially if this remote learning situation continues into next fall.

I remember back in seventh grade when some friends and I tried to break down the cost of Pingry life into an hourly rate. It came down to about $30 an hour, and we joked about how much we were getting robbed by DEAR time––but even back then I think we understood this metric wasn’t the end-all-be-all. The years since have only affirmed that for me: in a normal Pingry hour, you’re getting a lot more than what’s on the schedule. In fact, I would argue that most of Pingry’s value comes down to the stuff you don’t expect: the triumphs and the failures, the conversations, the relationships, the journey as a whole. We cannot and should not try to assign dollar values to those kinds of experiences.

Such is the paradox of the educational product: for students, the beneficiaries, Pingry is a priceless experience, but for our parents, the customers, it is a hefty investment with a fairly clear goal: “success” in a high-quality educational environment. In my experience, the student and parent perspectives mix like oil and water––where the external parental perspective sees a clear-cut result, the internal student perspective sees the fruits of a complicated learning process.

The issue we now face critically disrupts the learning process and the experience as a whole, which makes it much easier for students and parents alike to take a critical stance on Pingry as a product. Of course, we are fighting it. We are trying our best to believe in the intangibly valuable educational community, and to an extent, we’re succeeding … but at the end of the day, Google Hangouts can’t replace the little things that make real school real: the fast-paced conversation of class, the small talk with teachers, the time with friends, the work-home separation. A screen can’t project all those priceless dimensions of the Pingry experience.

But can we prorate the priceless? Can we somehow reimburse students for the intangible education that they lost, while still keeping faculty paychecks running? The answer, especially in the wake of this unforeseen disruption, is probably no. Neither universities nor private high schools have even entertained the concept, citing the argument that, despite the drop in quality, they are still doing their best to provide educational resources remotely. That being said, if school is unable to resume in the fall, that changes the game, since tuition adjustment would be an act of foresight on behalf of a “new” product rather than an after-the-fact reaction in the midst of chaotic change.

In any case, there are two requests we as students can and should make, in the event that remote learning extends to the rest of this year and potentially beyond.

- For the Board of Trustees: please prorate our Sage Dining meal plans. If we are not receiving a service that our parents paid for, we deserve reimbursement. In addition, please consider the prospect of “prorating the priceless,” for both this semester and, if need be, next semester––even if other institutions have dismissed this idea, it is certainly worth deducing and communicating its viability.

- For Mr. Levinson: please address both parents and the student body on this topic. Tuition matters, and in times like this, when the product of Pingry is being tested in unforeseen ways, it ought not to be taboo.

The prospect of refunding some portion of school costs is a matter of goodwill and care for the community. It is the kind of action that recognizes the state of our education not only as a journey in life but as a financial investment that ought to be respected.

Mar 29, 2020 | Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

Lights. Silence. 390 seconds of glory.

Ever since I first watched in sixth grade, I knew I wanted to do LeBow.

From the win of Katie Coyne ‘16 to the two-year reign of Rachel Chen ‘18 to the triumph of Miro Bergam ‘19, I sat anxiously in the audience year after year. I was the nervous yet critical viewer, who, in his endless deification of the stage, kept imagining how he himself might fare or fail in front of 700 academics. Time flew like an arrow, from imagination to reality. In my sophomore year, I took the stage with a speech about memes. And I won.

The aftermath followed a rapid progression from satisfaction to excitement to terror. I achieved what I had dreamed of for years, and I could still look forward to another chance at the stage in 2020. But I also knew I could very easily fail that second chance and fall short of the high expectations.

In preparing for this year’s competition, I believed that the only way to successfully replay the game would be to break it. So I chose to call out the unsettling pattern of universal agreeability that LeBow speeches were developing, a problematic pattern I myself upheld the year before. In this sense the speech was a critical self-reflection––I chose to burn the magic that I had internalized and glorified over the years, and from those ashes construct an argument against the very anti-argument nature of Pingry culture I embraced.

Did I fail? Certainly in the sense of losing the title.

But in retrospect, I got what I asked for. I did not design my speech to maximize likability among a judging panel––I wrote it in order to spark critical thought and disagreement among the broader student community. And in that sense, I think it was a success.

I met two counterarguments that, in the spirit of debate, I want to address.

To reiterate, my thesis is as follows:

“In order to make sure students develop the key skills of political disagreement, we ought to bring timely, wholehearted, messy debates into the classroom––and then we students ought to embrace more of that argumentative style in our own independent endeavors [eg LeBow itself].”

1. My message is NOT that Pingry students lack the capability to have difficult discussions. I can’t speak for what goes on within specific environments like affinity groups. I simply question how far-reaching, especially between identity boundaries, these discussions are. Thus, I assert that the humanities classroom is the best place to make controversial discussions informed and ubiquitous. Otherwise, Pingry students, like most citizens, will naturally flock to echo chambers, and schoolwide communication, especially in assemblies, will continue to favor numbing agreeability and “political correctness.”

2. Yes, I do think teachers should give their personal opinions in class. Obviously, this comes with a two-pronged expectation of maturity. The student should be able to respect the teacher’s opinion without bowing down to it, and the teacher should be able to be subjective with the explicit intent to inform rather than directly convince.

As I defend this thesis, I don’t pretend my speech was perfect. I made plenty of miscalculations, the most obvious of which was the exclamation that “I’m the Big Fish in a Little Pingry Pond!” Yes, that sounds arrogant. I was trying to be ironic, I was trying to make it clear that the concept of a big fish here is a dangerous illusion that limits one’s ability to think outside the scope of this community’s limited discourse. But I suppose using such a phrase as the cornerstone of the speech might have given some pretty negative impressions. So it goes.

It’s over now. Now I will return to the audience for one last year to watch the brilliance of LeBow from a new lens. But I won’t forget the message I crafted. I’ll continue to defend it and live it out, especially in regards to this newspaper.

The theory of the Big Fish was refuted. But defeated? The point was made on stage and proven offstage. So I accept this loss wholeheartedly.

Feb 25, 2020 | Editorial, Meghan Durkin, Opinion

By Meghan Durkin (V)

It’s February 1979. The phone rings. The clock reads 3 a.m. as my grandfather holds it up to his ear. It’s 11:30 a.m. in Iran, where the Shah, Mohammad Raza Pahlavi, had fled in response to insurgency a month earlier. At the time, my grandfather was working for American Bell International, an AT&T subsidiary tasked with facilitating the improvement of telephone and communication systems in Iran. However, with the overthrow of Pahlavi and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini, AT&T’s project ceased. Over the next few weeks, my grandfather, who handled insurance for the company, worked to repossess valuables left by AT&T employees, who were forced to leave their apartments in Iran following the fall of the Shah. After finding where workers had left clothing, jewelry, pets, and more, my grandfather transferred that information to employees still in Iran, in hopes of reclaiming their belongings.

Prior to the winter of 1979, during the height of AT&T’s project in Iran, U.S. relations with the country were bolstered. The pro-Western policies of Pahlavi fit American economic interests, specifically in regards to the oil industry. However, to many Iranians, the Shah’s policies felt repressive and tyrannical. The “White Revolution,” a number of reforms established by Pahlavi in the early 1960s, implemented land redistribution, and the expansion of women’s rights. These policies were quickly met with popular dissent, as the poor found little relief. By the end of the Shah’s reign, the U.S. appeared to support a leader unpopular with his own people. Once Pahlavi fled, his favorable relations with the U.S. seemed to continue, much to the resentment of Iranians. U.S. President Jimmy Carter went so far as to allow Pahlavi into the U.S. to receive cancer treatment.

In November of 1979, in retaliation for Carter’s action, Iranian students took 66 Americans hostage at the U.S Embassy in the Iranian capital of Tehran. The crisis, which lasted 344 days but ultimately ended in the safe return of the hostages, began a long history of strained relations between the U.S. and Iran.

These historic tensions were in the spotlight this January, when President Trump ordered an airstrike that killed Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. After the strike, Trump threatened to carry out further attacks. On Twitter, he referred back to the 1979 crisis, noting that the 52 Iranian sites that had been identified as targets represented “the 52 American hostages taken by Iran many years ago.” Many Iranians, who considered Soleimani a hero, were quick to declare revenge and violence against the U.S. However, President Trump and his administration have continued to justify the act as a preemptive attack against a supposed plan of Soleimani to strike a U.S. embassy.

Over 40 years after the overthrow of the Shah and the consequent American hostage crisis, U.S.-Iran relations seem rockier than ever. Under President Obama in 2013, the countries attempted reconciliation through the Iran Nuclear Deal, which outlined that Iran would restrict their nuclear activities. In 2018, however, President Trump abandoned the plan, and the two countries have faced growing tension and subsequent violence over the past few years. Now, after Soleimani’s death, there seems to be no end in sight.

Thus, the question remains: is compromise between the U.S. and Iran possible? Is an amicable relationship on the horizon, or will we continue towards aggression and animosity? To me, the two countries have grown too divisive to ever find a real compromise, and the U.S. does not have a compelling reason to concede to the Iranian government. When President George W. Bush coined Iran one-third of the “axis of evil,” it was clear the United States viewed the country’s regime as radical and dangerous; the government has been accused of supporting terrorism and seeking to bolster weapons of mass destruction. Thus, our government doesn’t owe the Iranian government diplomacy, but it does have a responsibility to support the Iranian people. As a result of economic sanctions placed on Iran in 2018, its people have faced an economic recession, rising prices, and stagnant economic growth. As innocent people suffer, the U.S. government seeks to break a regime, without thinking of the consequences for the average citizen. So, while I believe I will never see a time like my grandfather’s, where the United States and Iran came together for economic gain, I do believe it’s possible for our government to protect itself against Iranian threats while still treating the Iranian people humanely.

Dec 9, 2019 | Brynn Weisholtz, Editorial

By Brynn Weisholtz (VI)

At Pingry, a student’s academic coursework is primarily determined by the administration and follows a fairly regimented path. There is limited flexibility for a student to “choose” any portion of his or her schedule in the early years of high school. This rigidity is seen mostly during the freshman and sophomore years when students are expected to take core classes to meet Pingry’s requirements for graduation. With the exception of a few electives, such as Art Fundamentals or a second language, ninth and tenth grade schedules are overflowing with mandatory classes in math, English, history, science, and foreign language requirements. These packed schedules do not leave much room for signing up for more specialized classes.

While junior year allows for some wiggle room with course selection, there are still mandatory classes, like American Literature and the next math and language classes on a student’s respective track, that eleventh graders must take. The real change occurs senior year when no mandatory classes are required, and the course choices become abundant. For the first time as a Pingry student, I had the ability to select courses I truly wanted to take. AP Gov or AP Euro, Science in the 21st Century or Anatomy and Physiology, Greek Epic or Shakesphere, Spanish 6 or French 1. This was empowering.

Every class I am participating in this year is a class I chose to be in, with subject matter I wanted to explore. While I have always been happy to come to school, eager to share my insight in class, it wasn’t until this year that I felt everything align, allowing my innate curiosity to soar beyond my own expectations. This heightened sense of fulfillment can only be attributed to the personal interest I have in each class I selected. Sitting side-by-side with peers with similar interests, we seem more motivated to engage deeply in the subject matter.

Having the opportunity to finally spend my days studying material that sparks the most interest in me leaves me asking the question: why did it take so long to arrive at this point? Could I have benefited from having more choices earlier in my academic career? What experiences could have further shaped me into me? Rather than lament what could have been, I choose to look ahead and embrace what is and what will be.

That said, I believe it would be beneficial to explore offering additional electives to students starting freshman year as a way to broaden horizons and spark intellectual curiosity, which is inherently one of Pingry’s pillars. Who knows what class will inspire a young mind to thrive intellectually?

Dec 9, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam

By Noah Bergam (V)

When I was a little kid, I got angry when I heard my name. Noah. I heard the word ‘No.’ Somehow that just pushed me over the edge. My older siblings, realizing my dislike, would further taunt me by calling ShopRite ShopWrong. I would cry.

Now it’s more sophisticated. I cry a little inside when I see political arguments and platforms supported fervently in the negative.

Ralph Ellison’s anonymous namesake Invisible Man asked a simple question. “Could politics ever be an expression of love?” The quote reads quickly in the context of the chaotic unfolding of the novel. But when I read it, I stopped and realized this combination of words is powerful.

It comes back to me every month for the Democratic debates. As I’ve watched these candidates give their heartfelt pleads for their causes, I’ve gone through my own little evolution as a viewer.

When I first watched in June, I was amazed by how eloquently they all could speak, swinging from topic to topic with such ease and intensity. Each candidate presented their own style, playing different gambits and spinning sophisticated responses, tying it back to their audience. All on the spot. It blows me away. But … but what? The charm blurred with repetition? The candidates are all a bunch of phonies? Emails!? Perhaps. But the fundamental issue I see is not with any of the specific values they hold or policies they endorse. It’s about a frame of reference. Their tendency to express their stances in terms of the partisan negative rather than the general positive. The tendency is captured by the standby:

“I’m the candidate that can beat Donald Trump.”

There’s a use for this phrase in moderation. But it ought not to become a cornerstone argument of the party—2016 is proof that doesn’t work.

When this mindset of opposition takes over for a few questions, the stage curls into an echo chamber, where counterpoints that lean to the center are labelled as enemy territory.

This was especially evident in the July debate; when Warren and Sanders kept recycling a certain phrase, they were met with opposition.

John Delaney warned against taking away private health insurance. John Hickenlooper objected to the Green New Deal’s broad promises of government-funded jobs. Jake Tapper asked Bernie how much taxes will rise for his healthcare bill.

The same response kept ringing up: “stop using Republican talking points.”

The intent of this phrase, as I see it, is to paint criticism as illegitimate partisan attacks. It’s defense built from offense––take the hard questions, that many voters are interested in getting direct answers to, and mark it as Republican, Trumpian spam.

This attitude has continued monthly. Of course, it doesn’t ruin the entire debate––most major candidates have their shining moments of clarity––but it confuses the very intent of these debates, which is to give the candidates a chance to explain their policies and disagree, so that we viewers can determine their differences and make the most educated vote we can. What is not needed is a constant, propaganda-esque reminder of our unity against those dreaded Republicans!

At the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Michelle Obama famously said, “When they go low, we go high.” Do not weaken the potential of your vote by thinking only in terms of who you are beating out. Vote for a positive, progressive vision of the future, not simply an anti-Trump candidate.

But everyone––this is a lesson that transcends party lines. I don’t know if politics could be an expression of love, but I like to believe that the heavy focus on partisan differences and identity could be relieved. That politics can be less an expression of electability and more an expression of a concrete stance, a vision.

In short, ShopRite instead of ShopWrong.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Mirika Jambudi, Opinion, Uncategorized

By Mirika Jambudi (III)

The world I’m growing up in scares me to death. It seems like everywhere I look there is something to be afraid of. In fact, I’m almost fifteen and I just got permission this summer to ride my bike to my friend’s house. It’s only two blocks away, but I understand why. The world I’m growing up in is scary because it’s dangerous. I can’t tell you that it’s more dangerous than any other period in human history, but I can tell you this: we’re certainly more aware of it. The news flashes every day with new stories of gunmen, arson, murder, and scandal in our very own White House. That shadow in the corner of my eye, that’s danger. The creak on the stairs when I’m home alone, that’s danger. This constant fear bleeds into every single aspect of my life.

In school, we’ve had lockdown drills for as long as I can remember. An announcement is made, so we lock the doors, draw the blinds, huddle in the corner, and stay as silent as possible. For those 4-7 minutes, I examine my best friend’s shoelaces intently. I imagine what I would do, if at that very moment, the drill was real and a shooter barged into the classroom. I count the bricks on the wall. I wonder if this is what it felt like to live during the Cold War, diving under desks to take cover at the prospect of nuclear war. Then, I wonder why people believed that a wooden desk could stop an atomic bomb. Probably, I think, for the same reasons we draw the blinds and lock the doors. Ever since the shooting in Parkland, Florida, though, something has changed. Everything feels more real. The idea of a school shooting used to be almost nonexistent. Something that happened to those poor kids in Sandy Hook, but could never happen to us.

But the national uproar 5,000 miles away brought about changes reaching all the way to Pingry. Now, we have more detailed lockdown procedures. Recently, we had an assembly describing safety procedures, and our newly installed lockdown buttons in case of an emergency. We know what to do during lunch, during time between classes. We know that if there’s an emergency, we are to go into the nearest open classroom, let as many kids in as possible, lock all the doors, and hide. The threat has become omnipresent. It’s not far away and vague anymore, but something that could actually happen to us. Even in the bathroom stalls, the inner doors are plastered with laminated posters explaining what to do if someone is in the bathroom while a lockdown is in progress. It tells me what keywords to listen for to make sure the all-clear is legitimate. The danger of a school shooting stares me in the face while I use the bathroom. It’s an unfading feeling of unease, present even when I’m walking down the hall with a friend, goofing off like an average pair of freshmen. I see the security guards on duty keeping an eye on everything, watching for any signs of suspicious activity. I understand why they are there, of course, but it reminds me that nowhere is safe.

I live in the epitome of suburbia, so it’s strange to have this fear everywhere I go. We have become desensitized to shootings and gun violence, and barely react to the now daily reports of shootings. Everywhere is unsafe: first movie theaters, coffee shops, and retail stores, and now schools. For me, school is a place I look forward to going every day; however, some days, when I step off of that yellow Kensington bus, I feel afraid of the unknown, and I concoct imaginary emergency scenarios in my head. I have my parents on speed dial, as a “just-in-case.” I have a message in the notes section of my phone for my loved ones, should something actually happen to me, though the chances are slim. I really shouldn’t have to worry about this; I’m just your average high school freshman trying not to fail Spanish and science, binging rom-coms and Disney movies in her free time. We shouldn’t have to worry that when we leave our houses in the morning for school, it might be the last time our parents see us alive.

Our government should have stepped up on gun policies and implemented stricter gun laws years ago, right after the incident at Sandy Hook. How many more lives must be lost until our government takes charge? Our nation needs action, and it is long overdue.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Aneesh Karuppur (V)

9, 13, 15,16,19.

A math problem? Of sorts, yes. Except it extends beyond the scope of a simple one-period, ten-problem math test—it is something we deal with at Pingry daily.

Class sizes are one of the most important parts of an educational experience, but we talk about it the least. In fact, I have never heard anybody talk about class size during my two-and-a-half years at Pingry.

Of course, this is mostly justified. Pingry’s class sizes are significantly smaller than those in other schools, both public and private. Our student to faculty ratio is half of what it is in surrounding public schools and one third of the national average.

Smaller class sizes have long been linked to better academic performance and learning capabilities. For the same reason a private tutor is more helpful than a large group lesson, smaller class sizes allow for more individual attention. Pingry bills its class sizes as small enough to foster this connection between the faculty and other students, but not too small as to discourage collaboration and teamwork. Our school prides itself on these class size caps, which are featured prominently in multiple places on pingry.org. They are all centered around the same line: “keeping class sizes to 16 at the Lower School, 14 in the Middle School, and 13 in the Upper School.”

Earlier this year, I noticed that my science class seemed unusually large. This made me realize that not every class is as small as Pingry’s website claims. My science class, for example, has 16 students, which isn’t massive, but the lab always feels full. With more students, it is more difficult to provide attention to each individual student, regardless of how good a teacher is. When 65 minutes have to be divided up among more students than normal, the time per student ostensibly decreases.

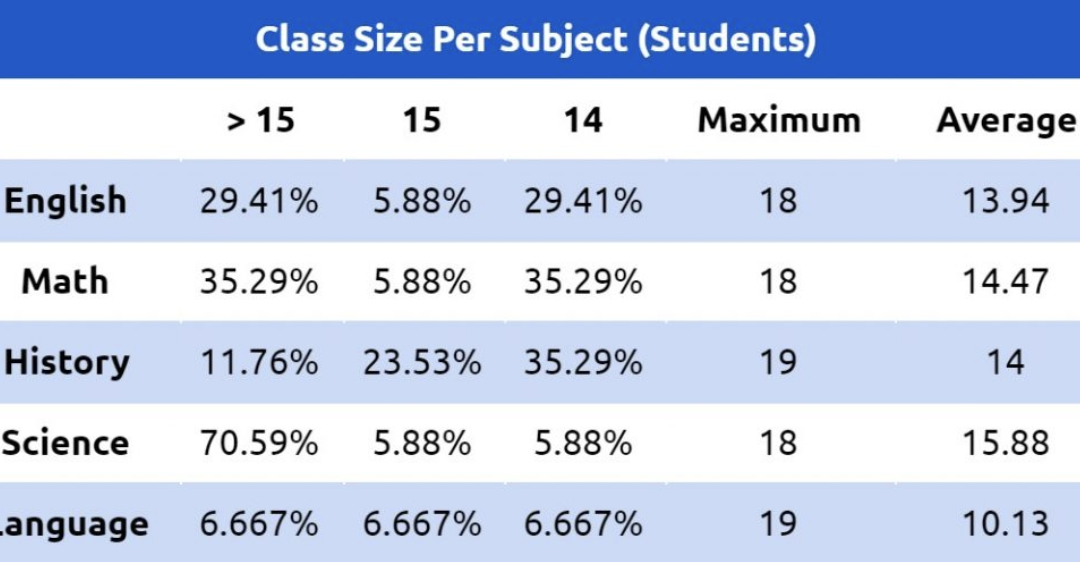

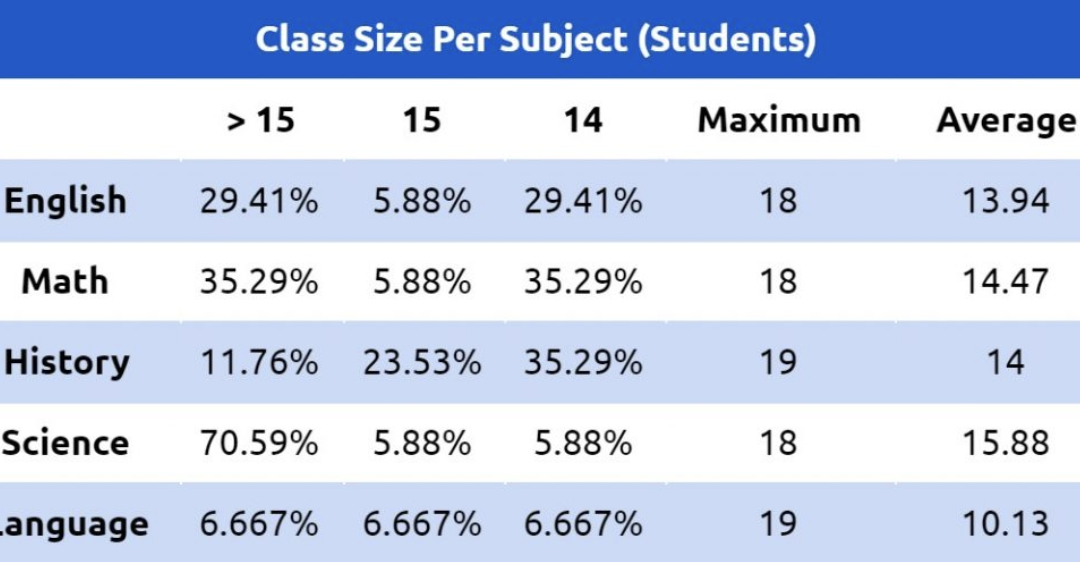

I wanted to make sure I wasn’t the only one noticing that class sizes are inching further away from that magic number 13. So, I created a survey that asked for the class size (including the teacher) of English, math, history, science, and language classes. I sent out the survey to various juniors and the entire Record staff. Out of the 17 people I polled, two reported not taking any language classes, so I ignored those two values when analyzing the data.

Based on this data, though, class size doesn’t really seem to be much of a problem. The averages are slightly higher than 13, with the exception of science classes, which are fairly higher. On the other hand, language classes seem particularly small.

This data doesn’t reveal the whole story though. The range of class sizes for each of these categories varies significantly: 10 for English, 12 for math, 9 for history, 5 for science, and 14 for languages.

This inconsistency led me to analyze each of the individual values themselves, shown in the table, which shows the percent of the sample with the class size of each category.

Clearly, a pattern has emerged. Language classes are mostly reasonably sized, besides one large class. History is the next best, with once again one very large class. English classes are in the middle of the pack, but the class size keeps increasing. Math classes are a little bit higher, but one class has a surprisingly large 20 students. Science classes exhibit the largest class sizes.

It’s understandable that not every class can be exactly 13 students, but to have almost three-quarters of science classes have more than 15 students is quite a stretch. In fact, not a single one of the science classes is less than 13 students; Pingry’s Science Department prides itself on its thorough explanation of concepts, but this disproportionate class size distribution hampers that proposition.

Now, I am in no way criticizing the faculty, staff, or administration. My point isn’t to criticize everyone except the students, but rather to note a trend that hurts our collective education.

Another important thing to note is that this is in no way a perfectly scientific survey. It is entirely possible that multiple students in this survey shared classes, which would skew the results. Misreporting could also have been a factor. My study also ignored electives and double subjects in science or math, for example. I definitely believe that further investigation should be done in order to ensure that class sizes are what they are supposed to be.

In this survey, I also asked for an ideal class size. The minimum was seven, and the maximum was 15 students. The average was 10.82 students per class. Obviously, classrooms and teachers don’t appear out of thin air, but some future thought needs to be given to what class size the average student might find beneficial.

Overall, there isn’t really much to panic about—just some intriguing numbers that show class sizes, especially in science, aren’t as low as they should be and that maybe the number 13 itself needs to be rethought a little bit. Perhaps 13 isn’t as magical as we believe.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Zara Jacob (V)

There are issues that everyone agrees are violations of the Honor Code: bullying, vandalism, racism, sexism, and so on and so forth. If any such disrespectful actions are committed, we unanimously cite the perpetrator’s betrayal of the Honor Code. We have a general consensus in this respect. However, there are some topics of contention among the student body when it comes to breaking the Honor Code, including—but definitely not limited to–– cheating, using Sparknotes, and breaking the dress code. Maybe when we students talk to teachers, administrators, or prospective parents, we have the facade of a united front, but I assure you, we have quite a spectrum of opinions ranging from very conservative to very rebellious.

Last year, I found out about someone cheating on a test. Now, when I say “cheating,” I do not mean “Sparknoting” Jane Eyre or telling someone that the test was easy or hard, but blatantly communicating the exact problems that would be on the test. I was shocked. I knew people looked at siblings’ tests or maybe knew the bonus question, but I was genuinely shocked by this incident. Sometimes we make fun of the Honor Code for being too idealistic or rigid, but was it really so naïve of me to believe that students would not actually cheat on a test? I will acknowledge that I am not a person who breaks a lot of rules, so maybe my shock is simply a consequence of my ignorance. However, I guess I expected that as a student body, we agreed upon, if nothing else, perhaps the most basic principle of the Honor Code: integrity. Then again, I did not report that person, so who am I to talk?

Let’s be completely candid about how many times we break the Honor Code each day, in our personal lives, in our academic lives, and in our extracurriculars. Are we all impeccable Pingry students that have upheld the contract we so earnestly signed on the first Friday of the school year?

No, we are not. I know that I am not. So how can I judge? How can I be so shocked? How can I write this 650-word rant about the Honor Code simply because someone cheated?

I can do this because I cannot pretend to be okay with people cheating. I got some of my lowest grades on the very tests the aforementioned person cheated on. I would study for hours, days before the test, dreading what types of questions were going to be asked. Meanwhile, that student was cruising, already having known the exact questions on the test. I wasn’t just appalled; I was infuriated. The message I’d been left with was this:

“Life’s not fair. Get used to it.”

It is unfortunate, but it could not be more true. Not everyone is going to follow the Honor Code; not in Pingry, not in college, and not in the real world.

I do not have a magical solution. I could end this opinion piece by saying that everyone should try to be good, and that we should try to make life fair by following the Honor Code to the best of our ability, but that would just further breach my integrity. The person who cheated will probably cheat again and get away with it. Pingry can make us sign all of the contracts in the world, have us write the Honor Pledge thousands of times, and have brilliant speakers for the Honor Board’s Speaker series, but the Honor Code at Pingry is, at its root, a suggestion—a highly recommended suggestion—but a suggestion nevertheless.

Follow the Honor Code, or don’t follow the Honor Code; the one truth I can tell you is that it comes down to you and the values you choose to have faith in.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Meghan Durkin, Opinion

By Meghan Durkin (V)

My brother joined me outside, football in hand. The fall wind brushed past our faces as it carried the ball from his hands to mine and back. Our hands grew colder with each toss until we ran inside for warmth. It was the first time we had thrown the football together in years. When we were younger, it was a weekly ritual, and one that brought us sweet memories. Five years later, standing in my backyard as the football flew through the chilling air, I felt the desire to reverse time. I wanted more than to be reminded of what we used to do; I wanted to be back in that time. I wished for my carefree, strong self; I needed my brother to have time to spend with me again.

I felt nostalgic. The feeling was overwhelmingly bittersweet. I envied my former self. The nostalgia consumed me. But I know I’m surely not alone in this feeling. Society has come to seek nostalgia more frequently. The feeling has shaped our media, trends, and fashion. Nostalgia, often a relatively personal feeling, has become global. The connectivity of our world, which has only recently expanded, forces commonalities in experiences that trigger nostalgia. With the rise of technology and social media, we have a greater access to shared thoughts and events, which ultimately allows nostalgia to shape our world as an image of the past.

This newfound sense of global nostalgia is evident in recent fashion trends: platform shoes from the seventies, scrunchies from the eighties, and the denim-on-denim look from the nineties. The popularity of these trends has resurfaced decades later to blend into today’s fashion. While acting as reminders of the past, they serve as evidence of the desire to return to and pull from what was. Nostalgia is also fueling the entertainment industry. In the last six months, Disney has released three live action remakes of their classic films, including Aladdin and The Lion King, which, combined, made over two billion dollars at the box office. These movies attracted people who had watched them as kids, capitalizing on the need for nostalgia. The films allow them to relive a simpler, often more desirable, time in their lives. Furthermore, both the resurfacing of fashion trends and classic movies stress the worldwide nature of nostalgia. It is felt universally by a generation. As distant places and people are connected through technology, that shared nostalgia is more accessible and society is reaching for it.

The accessibility of nostalgia is present in the popularity of Netflix. With the click of a button, people can watch shows and movies from decades ago. These shows, including Friends and The Office, are not only watched by original fans, but by a new generation who wishes to be included in the shows and the collective experience they create. Along with this, the Netflix revivals of shows such as Gilmore Girls and Arrested Development give viewers a greater entrance into the past as it seemingly takes them, in a new way, back to the first time they saw the show. For original viewers, this type of access to their favorite show has only been made possible recently.

While nostalgia allows fond times and experiences in our lives to resurface, it can be dangerous. Nostalgia acts as another form of regret, a form that is often sheltered from the negative connotations. The feeling stops us from letting go; it stops us from being satisfied. With expanding technology and connection, nostalgia is no longer as simple as reminiscing over tossing the football in the backyard; it is a way to expose the discontent with society in the present. People wish to go back to a time in which they believe the world was better off. The rise of global nostalgia signifies a collective need to remove ourselves from the present, and reminisce about the simpler times of our past.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam, Opinion

Noah Bergam (V)

In the spring of last year, some friends and I became obsessed with an online game called Diplomacy. In this wonderfully irritating game, each player owns a certain pre-WWI European country, and, move by move, they try to maximize their territory.

Since each player starts out with roughly the same resources, the only way to succeed is to make alliances, to get people to trust you, and, of course, to silently betray that trust at some point to reach the top.

This was perhaps the first time I was introduced to the concept of a zero-sum game––a system where, in order to gain, someone else must lose. I was terrible at it. I didn’t have the confidence to really scare anyone. I couldn’t keep a secret for my life. And worst of all, I couldn’t get anyone to trust me.

The ‘game’ I was most familiar with up to that point was that of school, of direct merit. A system where hard work and quality results are supposed to pay off on an individual basis, and one person’s success doesn’t have to mean another’s failure.

I was especially entrenched in that mindset when my brother went to Pingry. I looked up to his leadership and social abilities, his diplomacy essentially, and realized I could never be like him in that realm––I didn’t have the same sort of outward confidence and social cunning. All I could do was look at his numbers and try my best to one-up them; in my mind, that was the only way for me to prove I wasn’t inferior.

But now that brotherly competition is gone. And I have the leadership I’ve been working toward. And now I’m realizing that, from my current perspective, Pingry’s system of student leadership is not the game of direct merit I thought it was. I wouldn’t go so far to say it’s a bloodbath, zero sum-game, but there’s certainly an element of transaction, and therefore diplomacy, you have to master. Complex transactions of time and energy for club tenure and awards.

It’s really an economy of accolades, where the currency is our effort as students outside the classroom. We involve ourselves in activities and invest our time, of course, to do things we love, but there’s no denying that there’s an incentive to earn a title, a position of leadership that can be translated onto a resumé.

It’s an ugly mindset, but it unfortunately exists. And the ruling principle is merit diplomacy––for the underclassmen, a more merit-oriented rise through application processes and appointments, and for upperclassmen leaders, a need to balance the prerogatives and talents of constituent club members.

That diplomatic end for the student leader is taxing. You have to think in terms of your own defense when people doubt your abilities. You need to make sure people still invest time in what you run. You want respect. Friendship. But sometimes you can’t shake off the guilt of getting that position, because you know the anxious feeling of watching and waiting for that reward.

Now your mistakes are visible. Now you have to know why you have the position you have, and why others should follow you. You need legitimacy to hold on to what you have.

I’m the first junior editor-in-chief of this paper in recent memory. And I know that raises eyebrows to my counterparts who know my brother was editor-in-chief last year. I acknowledge that publicly, because I’m putting the integrity and openness of my job here above my own personal fear of being seen as some privileged sequel. I’m not going to let whispers define my work. I know who I am, and it’s more than just this title. It’s more than a well-spent investment in the economy of accolades. And I’ll prove it.

That’s what the diplomacy side of things teaches you. You come to a watershed moment in high school where you pass the illusion of the merit machine and realize it’s all a matter of communication.

Merit diplomacy can be an ugly and nerve wracking concept; it’s damaging to take it so seriously. It distracts from true passion, and it reinforces the bubble of Pingry life, making us deify our in-school positions and the idea of the accolade rather than the identity of the students themselves.

There are communities and worlds beyond this school. And one might think of Pingry’s economy of accolades as the microcosm of the ‘real world.’ But I think even that gives it too much credit.

It’s practice. It should be a side thought to our passions, not the intense focus of student life. Merit diplomacy is a game––perhaps a high-stakes game––but a game nonetheless.