Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Mirika Jambudi, Opinion, Uncategorized

By Mirika Jambudi (III)

The world I’m growing up in scares me to death. It seems like everywhere I look there is something to be afraid of. In fact, I’m almost fifteen and I just got permission this summer to ride my bike to my friend’s house. It’s only two blocks away, but I understand why. The world I’m growing up in is scary because it’s dangerous. I can’t tell you that it’s more dangerous than any other period in human history, but I can tell you this: we’re certainly more aware of it. The news flashes every day with new stories of gunmen, arson, murder, and scandal in our very own White House. That shadow in the corner of my eye, that’s danger. The creak on the stairs when I’m home alone, that’s danger. This constant fear bleeds into every single aspect of my life.

In school, we’ve had lockdown drills for as long as I can remember. An announcement is made, so we lock the doors, draw the blinds, huddle in the corner, and stay as silent as possible. For those 4-7 minutes, I examine my best friend’s shoelaces intently. I imagine what I would do, if at that very moment, the drill was real and a shooter barged into the classroom. I count the bricks on the wall. I wonder if this is what it felt like to live during the Cold War, diving under desks to take cover at the prospect of nuclear war. Then, I wonder why people believed that a wooden desk could stop an atomic bomb. Probably, I think, for the same reasons we draw the blinds and lock the doors. Ever since the shooting in Parkland, Florida, though, something has changed. Everything feels more real. The idea of a school shooting used to be almost nonexistent. Something that happened to those poor kids in Sandy Hook, but could never happen to us.

But the national uproar 5,000 miles away brought about changes reaching all the way to Pingry. Now, we have more detailed lockdown procedures. Recently, we had an assembly describing safety procedures, and our newly installed lockdown buttons in case of an emergency. We know what to do during lunch, during time between classes. We know that if there’s an emergency, we are to go into the nearest open classroom, let as many kids in as possible, lock all the doors, and hide. The threat has become omnipresent. It’s not far away and vague anymore, but something that could actually happen to us. Even in the bathroom stalls, the inner doors are plastered with laminated posters explaining what to do if someone is in the bathroom while a lockdown is in progress. It tells me what keywords to listen for to make sure the all-clear is legitimate. The danger of a school shooting stares me in the face while I use the bathroom. It’s an unfading feeling of unease, present even when I’m walking down the hall with a friend, goofing off like an average pair of freshmen. I see the security guards on duty keeping an eye on everything, watching for any signs of suspicious activity. I understand why they are there, of course, but it reminds me that nowhere is safe.

I live in the epitome of suburbia, so it’s strange to have this fear everywhere I go. We have become desensitized to shootings and gun violence, and barely react to the now daily reports of shootings. Everywhere is unsafe: first movie theaters, coffee shops, and retail stores, and now schools. For me, school is a place I look forward to going every day; however, some days, when I step off of that yellow Kensington bus, I feel afraid of the unknown, and I concoct imaginary emergency scenarios in my head. I have my parents on speed dial, as a “just-in-case.” I have a message in the notes section of my phone for my loved ones, should something actually happen to me, though the chances are slim. I really shouldn’t have to worry about this; I’m just your average high school freshman trying not to fail Spanish and science, binging rom-coms and Disney movies in her free time. We shouldn’t have to worry that when we leave our houses in the morning for school, it might be the last time our parents see us alive.

Our government should have stepped up on gun policies and implemented stricter gun laws years ago, right after the incident at Sandy Hook. How many more lives must be lost until our government takes charge? Our nation needs action, and it is long overdue.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Aneesh Karuppur (V)

9, 13, 15,16,19.

A math problem? Of sorts, yes. Except it extends beyond the scope of a simple one-period, ten-problem math test—it is something we deal with at Pingry daily.

Class sizes are one of the most important parts of an educational experience, but we talk about it the least. In fact, I have never heard anybody talk about class size during my two-and-a-half years at Pingry.

Of course, this is mostly justified. Pingry’s class sizes are significantly smaller than those in other schools, both public and private. Our student to faculty ratio is half of what it is in surrounding public schools and one third of the national average.

Smaller class sizes have long been linked to better academic performance and learning capabilities. For the same reason a private tutor is more helpful than a large group lesson, smaller class sizes allow for more individual attention. Pingry bills its class sizes as small enough to foster this connection between the faculty and other students, but not too small as to discourage collaboration and teamwork. Our school prides itself on these class size caps, which are featured prominently in multiple places on pingry.org. They are all centered around the same line: “keeping class sizes to 16 at the Lower School, 14 in the Middle School, and 13 in the Upper School.”

Earlier this year, I noticed that my science class seemed unusually large. This made me realize that not every class is as small as Pingry’s website claims. My science class, for example, has 16 students, which isn’t massive, but the lab always feels full. With more students, it is more difficult to provide attention to each individual student, regardless of how good a teacher is. When 65 minutes have to be divided up among more students than normal, the time per student ostensibly decreases.

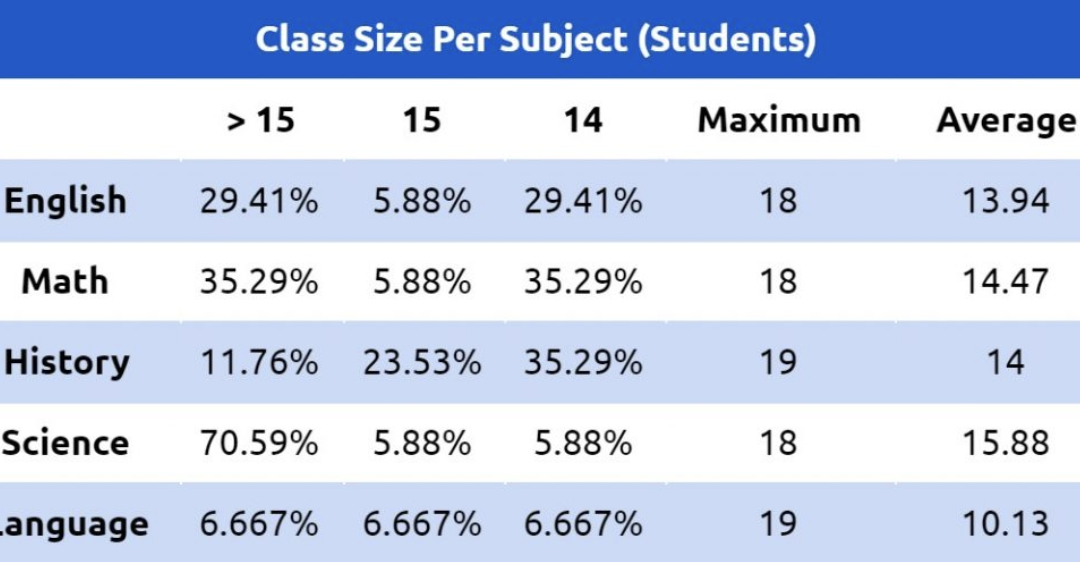

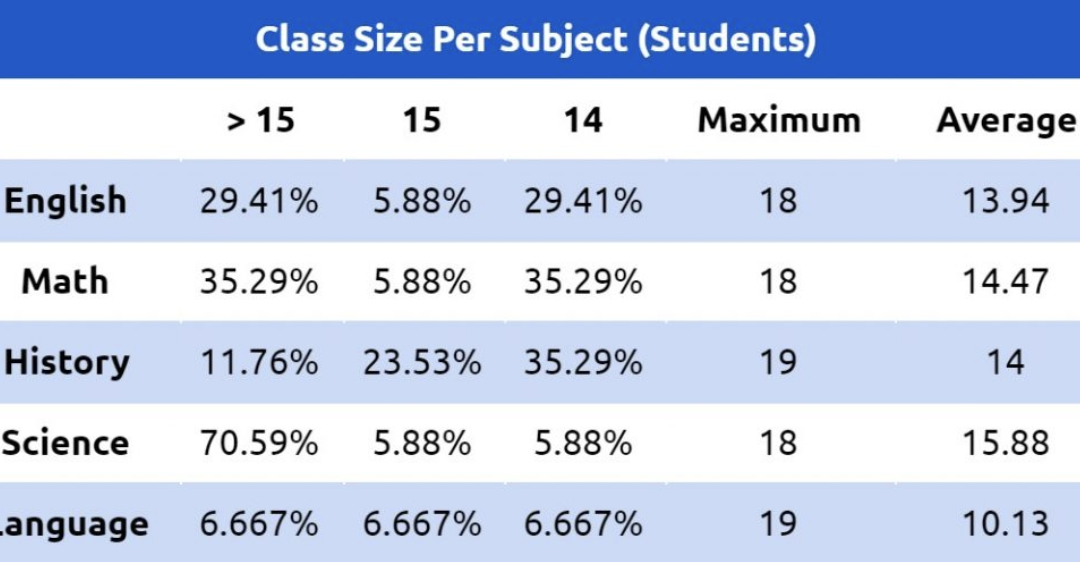

I wanted to make sure I wasn’t the only one noticing that class sizes are inching further away from that magic number 13. So, I created a survey that asked for the class size (including the teacher) of English, math, history, science, and language classes. I sent out the survey to various juniors and the entire Record staff. Out of the 17 people I polled, two reported not taking any language classes, so I ignored those two values when analyzing the data.

Based on this data, though, class size doesn’t really seem to be much of a problem. The averages are slightly higher than 13, with the exception of science classes, which are fairly higher. On the other hand, language classes seem particularly small.

This data doesn’t reveal the whole story though. The range of class sizes for each of these categories varies significantly: 10 for English, 12 for math, 9 for history, 5 for science, and 14 for languages.

This inconsistency led me to analyze each of the individual values themselves, shown in the table, which shows the percent of the sample with the class size of each category.

Clearly, a pattern has emerged. Language classes are mostly reasonably sized, besides one large class. History is the next best, with once again one very large class. English classes are in the middle of the pack, but the class size keeps increasing. Math classes are a little bit higher, but one class has a surprisingly large 20 students. Science classes exhibit the largest class sizes.

It’s understandable that not every class can be exactly 13 students, but to have almost three-quarters of science classes have more than 15 students is quite a stretch. In fact, not a single one of the science classes is less than 13 students; Pingry’s Science Department prides itself on its thorough explanation of concepts, but this disproportionate class size distribution hampers that proposition.

Now, I am in no way criticizing the faculty, staff, or administration. My point isn’t to criticize everyone except the students, but rather to note a trend that hurts our collective education.

Another important thing to note is that this is in no way a perfectly scientific survey. It is entirely possible that multiple students in this survey shared classes, which would skew the results. Misreporting could also have been a factor. My study also ignored electives and double subjects in science or math, for example. I definitely believe that further investigation should be done in order to ensure that class sizes are what they are supposed to be.

In this survey, I also asked for an ideal class size. The minimum was seven, and the maximum was 15 students. The average was 10.82 students per class. Obviously, classrooms and teachers don’t appear out of thin air, but some future thought needs to be given to what class size the average student might find beneficial.

Overall, there isn’t really much to panic about—just some intriguing numbers that show class sizes, especially in science, aren’t as low as they should be and that maybe the number 13 itself needs to be rethought a little bit. Perhaps 13 isn’t as magical as we believe.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Zara Jacob (V)

There are issues that everyone agrees are violations of the Honor Code: bullying, vandalism, racism, sexism, and so on and so forth. If any such disrespectful actions are committed, we unanimously cite the perpetrator’s betrayal of the Honor Code. We have a general consensus in this respect. However, there are some topics of contention among the student body when it comes to breaking the Honor Code, including—but definitely not limited to–– cheating, using Sparknotes, and breaking the dress code. Maybe when we students talk to teachers, administrators, or prospective parents, we have the facade of a united front, but I assure you, we have quite a spectrum of opinions ranging from very conservative to very rebellious.

Last year, I found out about someone cheating on a test. Now, when I say “cheating,” I do not mean “Sparknoting” Jane Eyre or telling someone that the test was easy or hard, but blatantly communicating the exact problems that would be on the test. I was shocked. I knew people looked at siblings’ tests or maybe knew the bonus question, but I was genuinely shocked by this incident. Sometimes we make fun of the Honor Code for being too idealistic or rigid, but was it really so naïve of me to believe that students would not actually cheat on a test? I will acknowledge that I am not a person who breaks a lot of rules, so maybe my shock is simply a consequence of my ignorance. However, I guess I expected that as a student body, we agreed upon, if nothing else, perhaps the most basic principle of the Honor Code: integrity. Then again, I did not report that person, so who am I to talk?

Let’s be completely candid about how many times we break the Honor Code each day, in our personal lives, in our academic lives, and in our extracurriculars. Are we all impeccable Pingry students that have upheld the contract we so earnestly signed on the first Friday of the school year?

No, we are not. I know that I am not. So how can I judge? How can I be so shocked? How can I write this 650-word rant about the Honor Code simply because someone cheated?

I can do this because I cannot pretend to be okay with people cheating. I got some of my lowest grades on the very tests the aforementioned person cheated on. I would study for hours, days before the test, dreading what types of questions were going to be asked. Meanwhile, that student was cruising, already having known the exact questions on the test. I wasn’t just appalled; I was infuriated. The message I’d been left with was this:

“Life’s not fair. Get used to it.”

It is unfortunate, but it could not be more true. Not everyone is going to follow the Honor Code; not in Pingry, not in college, and not in the real world.

I do not have a magical solution. I could end this opinion piece by saying that everyone should try to be good, and that we should try to make life fair by following the Honor Code to the best of our ability, but that would just further breach my integrity. The person who cheated will probably cheat again and get away with it. Pingry can make us sign all of the contracts in the world, have us write the Honor Pledge thousands of times, and have brilliant speakers for the Honor Board’s Speaker series, but the Honor Code at Pingry is, at its root, a suggestion—a highly recommended suggestion—but a suggestion nevertheless.

Follow the Honor Code, or don’t follow the Honor Code; the one truth I can tell you is that it comes down to you and the values you choose to have faith in.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Meghan Durkin, Opinion

By Meghan Durkin (V)

My brother joined me outside, football in hand. The fall wind brushed past our faces as it carried the ball from his hands to mine and back. Our hands grew colder with each toss until we ran inside for warmth. It was the first time we had thrown the football together in years. When we were younger, it was a weekly ritual, and one that brought us sweet memories. Five years later, standing in my backyard as the football flew through the chilling air, I felt the desire to reverse time. I wanted more than to be reminded of what we used to do; I wanted to be back in that time. I wished for my carefree, strong self; I needed my brother to have time to spend with me again.

I felt nostalgic. The feeling was overwhelmingly bittersweet. I envied my former self. The nostalgia consumed me. But I know I’m surely not alone in this feeling. Society has come to seek nostalgia more frequently. The feeling has shaped our media, trends, and fashion. Nostalgia, often a relatively personal feeling, has become global. The connectivity of our world, which has only recently expanded, forces commonalities in experiences that trigger nostalgia. With the rise of technology and social media, we have a greater access to shared thoughts and events, which ultimately allows nostalgia to shape our world as an image of the past.

This newfound sense of global nostalgia is evident in recent fashion trends: platform shoes from the seventies, scrunchies from the eighties, and the denim-on-denim look from the nineties. The popularity of these trends has resurfaced decades later to blend into today’s fashion. While acting as reminders of the past, they serve as evidence of the desire to return to and pull from what was. Nostalgia is also fueling the entertainment industry. In the last six months, Disney has released three live action remakes of their classic films, including Aladdin and The Lion King, which, combined, made over two billion dollars at the box office. These movies attracted people who had watched them as kids, capitalizing on the need for nostalgia. The films allow them to relive a simpler, often more desirable, time in their lives. Furthermore, both the resurfacing of fashion trends and classic movies stress the worldwide nature of nostalgia. It is felt universally by a generation. As distant places and people are connected through technology, that shared nostalgia is more accessible and society is reaching for it.

The accessibility of nostalgia is present in the popularity of Netflix. With the click of a button, people can watch shows and movies from decades ago. These shows, including Friends and The Office, are not only watched by original fans, but by a new generation who wishes to be included in the shows and the collective experience they create. Along with this, the Netflix revivals of shows such as Gilmore Girls and Arrested Development give viewers a greater entrance into the past as it seemingly takes them, in a new way, back to the first time they saw the show. For original viewers, this type of access to their favorite show has only been made possible recently.

While nostalgia allows fond times and experiences in our lives to resurface, it can be dangerous. Nostalgia acts as another form of regret, a form that is often sheltered from the negative connotations. The feeling stops us from letting go; it stops us from being satisfied. With expanding technology and connection, nostalgia is no longer as simple as reminiscing over tossing the football in the backyard; it is a way to expose the discontent with society in the present. People wish to go back to a time in which they believe the world was better off. The rise of global nostalgia signifies a collective need to remove ourselves from the present, and reminisce about the simpler times of our past.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Noah Bergam, Opinion

Noah Bergam (V)

In the spring of last year, some friends and I became obsessed with an online game called Diplomacy. In this wonderfully irritating game, each player owns a certain pre-WWI European country, and, move by move, they try to maximize their territory.

Since each player starts out with roughly the same resources, the only way to succeed is to make alliances, to get people to trust you, and, of course, to silently betray that trust at some point to reach the top.

This was perhaps the first time I was introduced to the concept of a zero-sum game––a system where, in order to gain, someone else must lose. I was terrible at it. I didn’t have the confidence to really scare anyone. I couldn’t keep a secret for my life. And worst of all, I couldn’t get anyone to trust me.

The ‘game’ I was most familiar with up to that point was that of school, of direct merit. A system where hard work and quality results are supposed to pay off on an individual basis, and one person’s success doesn’t have to mean another’s failure.

I was especially entrenched in that mindset when my brother went to Pingry. I looked up to his leadership and social abilities, his diplomacy essentially, and realized I could never be like him in that realm––I didn’t have the same sort of outward confidence and social cunning. All I could do was look at his numbers and try my best to one-up them; in my mind, that was the only way for me to prove I wasn’t inferior.

But now that brotherly competition is gone. And I have the leadership I’ve been working toward. And now I’m realizing that, from my current perspective, Pingry’s system of student leadership is not the game of direct merit I thought it was. I wouldn’t go so far to say it’s a bloodbath, zero sum-game, but there’s certainly an element of transaction, and therefore diplomacy, you have to master. Complex transactions of time and energy for club tenure and awards.

It’s really an economy of accolades, where the currency is our effort as students outside the classroom. We involve ourselves in activities and invest our time, of course, to do things we love, but there’s no denying that there’s an incentive to earn a title, a position of leadership that can be translated onto a resumé.

It’s an ugly mindset, but it unfortunately exists. And the ruling principle is merit diplomacy––for the underclassmen, a more merit-oriented rise through application processes and appointments, and for upperclassmen leaders, a need to balance the prerogatives and talents of constituent club members.

That diplomatic end for the student leader is taxing. You have to think in terms of your own defense when people doubt your abilities. You need to make sure people still invest time in what you run. You want respect. Friendship. But sometimes you can’t shake off the guilt of getting that position, because you know the anxious feeling of watching and waiting for that reward.

Now your mistakes are visible. Now you have to know why you have the position you have, and why others should follow you. You need legitimacy to hold on to what you have.

I’m the first junior editor-in-chief of this paper in recent memory. And I know that raises eyebrows to my counterparts who know my brother was editor-in-chief last year. I acknowledge that publicly, because I’m putting the integrity and openness of my job here above my own personal fear of being seen as some privileged sequel. I’m not going to let whispers define my work. I know who I am, and it’s more than just this title. It’s more than a well-spent investment in the economy of accolades. And I’ll prove it.

That’s what the diplomacy side of things teaches you. You come to a watershed moment in high school where you pass the illusion of the merit machine and realize it’s all a matter of communication.

Merit diplomacy can be an ugly and nerve wracking concept; it’s damaging to take it so seriously. It distracts from true passion, and it reinforces the bubble of Pingry life, making us deify our in-school positions and the idea of the accolade rather than the identity of the students themselves.

There are communities and worlds beyond this school. And one might think of Pingry’s economy of accolades as the microcosm of the ‘real world.’ But I think even that gives it too much credit.

It’s practice. It should be a side thought to our passions, not the intense focus of student life. Merit diplomacy is a game––perhaps a high-stakes game––but a game nonetheless.

Oct 18, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

Justin Li (V)

Traditionally, the process of education has been regarded as the unreciprocated transfer of information to a student, who is treated as an empty container to be filled. Paulo Freire, a 20th-century philosopher on pedagogy, refers to this antiquated model as “banking education,” which he demonstrates as discouraging to critical thinking and creativity.

In recent years, society has begun to progress from its sole reliance on memorization and one-sided lecturing towards what Freire calls a “problem-posing model,” which characterizes education as a mutually beneficial barter of knowledge between teacher and student. Through conversations with students attending high school in different parts of the world, I’ve realized that Pingry is on the cutting edge of this evolution.

In other words, at least at Pingry, students should no longer view their teachers as distant faucets of information. More and more, the student’s relationship with their teachers is becoming an exchange in which both sides participate equally. In the same way that a teacher confers their own knowledge, they encourage the expression of the student’s own ideas, even when they counter their own. However, this model — one in which it is possible for the student to teach the teacher—inherently blurs the roles that their very titles suggest; an effective problem-posing teacher invites this lack of distinction in the classroom.

Any schools which uses the problem posing model must also face the practical implications of a more egalitarian relationship between the teacher and student. Though in abstract, such a relationship should promote an education based on critical thinking, a lack of boundaries can create a potential for abuse of power, conflicts of interest, and other forms of misconduct.

Beyond the relative security that watchful students and teachers provide within the peripheries of the Pingry campus, these issues are compounded. For instance, what can we categorize as appropriate mediums of external communication? Pingry students reach out to faculty through their Pingry email addresses. The formality of typical email conventions, as well as the fact that all correspondence occurs under a “pingry.org” domain, makes this choice the standard. The nature of an alternate method of communication, such as text messaging, is more of a grey area; it elicits the use of abbreviations, emojis, and a relatively informal tone. Text messaging is the primary means of communication for most of the students I know, and likely the same for many teachers. Thus, texting seems more natural a medium of communication for almost all of us, as it feels more like a conversation than a series of inquiries. The topic and frequency of external communication is also important to consider. When a teacher and a student share an interest in the same NBA team, or both enjoy biking as a hobby, is it inappropriate for them to speak about it outside of school occasionally? How about every week? If both teacher and student feel entirely comfortable during the interaction, has a boundary been crossed?

In many cases, I don’t believe so. Whether it be through the tone of the conversation or a common hobby, a certain kind of respect accompanies a student’s ability to relate with his teacher. For example, I don’t believe that the sole act of texting a student is necessarily inappropriate, even about nonacademic subjects. However, it is essential to understand that harmless familiarity can quickly lead to being uncomfortable. Pingry’s administrators should make an effort to more clearly establish the details of this boundary to both faculty and students, and ensure that violations are identifiable, without question. Whether these boundaries align exactly with the ones I’ve presented above is not as important as ensuring their clarity for all members of the community. In practice, a good start to this goal might look like a formal assembly outlining these boundaries, accompanied by an accessible email or document.

In short, I believe that in order to create an environment that is both conducive to learning and comfortable for students, it is the administration’s paramount duty to draw and enforce teacher-student boundaries. At Pingry, violations of these boundaries have been treated with gravity and resolved with exemplary speed. Simultaneously, though at a lesser degree, we must value the educational benefits of an empathetic relationship. We should recognize that students and teachers should not be as detached from each other as they traditionally were. In fact, with strict barriers, we should embrace the fact that teachers and students are more alike than we think.

Mar 24, 2019 | Brynn Weisholtz, Editorial, Opinion

By Brynn Weisholtz ’20

Standing in line to see Come From Away at the Schoenfeld Theater in New York City, I found myself wishing I were on a different line waiting for basically any other show. I peered around at the other shows near me. I saw Dear Evan Hansen and sighed; Kinky Boots and smiled; Hamilton and gasped. Indeed, I knew nothing about Come From Away except that my mother had met an older woman at Dear Evan Hansen who raved about it and convinced her to catapult Come From Away to the top of our Broadway wish list.

As the doors opened at 7:30, the line filed into the smallest theater I had ever been in. My family took our seats and, as I looked around, I noticed that the average age of the audience was somewhere between the ages of my parents and my grandparents. Suddenly, I heard a woman explaining that she and her husband had flown into New York City from Newfoundland this very morning to see the play. As the lights began to dim, my curiosity was piqued by her story; she had, in fact, lived through some of the events that were to be featured in the musical.

I knew Come From Away centered around the small town of Gander in Newfoundland, Canada, where an intimate community rallied to help strangers following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. However, I did not have any concept of how the tragic events of the day forever changed the lives of the selfless people of Gander. With air traffic halted and planes unable to land in the United States, 38 planes were diverted to Gander Airport, and Gander, with a population of only 9,000, welcomed over 7,000 strangers from across the world with open arms. At a moment’s notice, cots were set up in schools, supplies were retrieved from local stores, food was prepared, and no questions were asked except, “What else can I do?”

I was truly in awe of all the people who opened their hearts and homes to complete strangers. The residents of Gander welcomed citizens from all walks of life and were not deterred by language or cultural barriers; instead, they bonded, embraced one another, celebrated life, and mourned the world’s tragedy alongside strangers, some of whom would become lifelong friends.Throughout the 100-minute musical, I was entranced by the story depicted on stage, one that brought both laughter and tears to my fellow onlookers and myself. While the majority of the audience appeared to vividly remember the events of 9/11, I only know of that day through second hand stories, as I was not yet born. Growing up in a post-9/11 world, I cannot fully comprehend how different life used to be, but the musical brought me to a better understanding of how radically the world around me has changed. Although I was not alive that fateful September morning, the tears I shed at the performance of Come From Away connected me with the people in that theater just as the people of Gander connected with their visitors. The show I regretted leaving my house for opened my eyes to see how selfless humans can truly be.

Mar 24, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Ethan Malzberg ’19

I grew up with a life-size band-aid covering wounds it never healed.

Though the expanse of years has erased much from my memory, I’ve never forgotten any of the comments on my gay voice. The first was in fifth grade. I beat him in a game of War, to which he responded, “At least I don’t have a gay voice!” It was a word still foreign to me, only heard on commercials for Modern Family, but it has altered the way I view myself even to this day. In a term I learned from Dr. Rodney Glasgow at the Student Diversity Leadership Conference, it was cognitive dissonance — an “identity bump” — with one comment completely changing my own perception of my identity in a way I had never considered before.

I ran home to my mom that day, impatient to tell her what that boy said. After a brief pause, she delivered the normal parental recourse for when your kid is bullied: “You’re not gay, he’s just trying to insult you because he’s jealous. Don’t let him bring you down!” It was a relief to hear this from my mother at the time: I was not the unfamiliar word with which he described my voice because my mom said so. It was a little band-aid to shield an enormous insecurity that has stalked me since.

It was also a relief to hear my guidance counselor repeat the same sentiment the following day. “You’re not gay, he’s just trying to insult you because he’s jealous. Don’t let him bring you down!” It was the perfect recipe for repression; I could now ignore his comment for the foreseeable future because my mom and guidance counselor said so. That is, of course, until the next “your voice is gay” would come just two months later at camp. Although the band-aid’s effect was fleeting, it was just what I needed at the time.

Years later, I discovered an email chain between my mother and my guidance counselor about the incident. “[Redacted] called Ethan’s voice ‘gay’ today,” my mother explained to the guidance counselor. “Of course, Ethan is not gay, but he was very hurt,” she finished. As I observe that exchange today, I gawk at how the situation was handled. “You’re not gay”: not then, but now I am. “He’s just trying to insult you”: how is it an insult? “Don’t let him bring you down”: you just did! The truth is my voice is higher pitched than the average male. It always has been and it always will be; I recognize there is nothing wrong with this but my lasting insecurity tells me otherwise.

Instead of addressing reality, adults put a band-aid of denial over this wound. People commented on my voice throughout the entirety of my childhood — even the rabbi at my own Bar Mitzvah joked that it was “angelic” and “womanly” during his sermon, and the panacea has always been, “That’s not true! Your voice is normal.” Every time a band-aid was put on me, it was promptly ripped off, reapplied, ripped off, reapplied. An interminable cycle that all but begged the wound to fester.

I don’t blame my mom or my guidance counselor at all — or any adult for that matter, since the same situation arose more times than I can count and touched all areas of my being. Shifting societal attitudes over the past eight years have changed the conversation on how to raise LGBTQ+ kids and I believe that email exchange would have been very different today. Regardless, every adult who recoursed the bullying I endured had the best intentions to make me feel better.

This Band-Aid Culture extends much further than my situation. It reminds me of the trophy debate: should every kid on every team be awarded a trophy? We subliminally tell the youth that everyone is the best even if they aren’t. In principle, this guards children from an unwarranted inferiority complex. In reality, we raise children to believe that the sole point of a game is to win. We prescribe trophies as band-aids to the losers, telling them “you are not a loser” instead of “it’s okay to lose, there is a greater purpose to the game than winning.” Though not a perfect analogy to my situation, like trophies, adults slapped on a band-aid to my troubles, telling me “you are not gay” instead of “love yourself no matter who you are.” Using band-aids, we shield kids from pain at the expense of growth. The wound never heals; instead, it festers until it reaches its nadir, and eventually, it must be treated properly. We need to eliminate the band-aids and start handling issues at the onset.

Mar 24, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Martha Lewand ’20

It may be hard to believe, but I recently had an interesting revelation when I took the ACT. Of course, most students consider the test both stressful and painful – it is a quintuple whammy of English, math, reading, science, and the essay. By the time I started to write that essay, I was thinking more about completing it than having a profound insight. But something about the essay got me thinking. Among other things, the prompt asked me to consider the perspective that we should block out as much bad news as we can, because too much negativity can lead people to believe that they can never solve the world’s problems. While that idea was initially appealing – after all, who wants to listen to bad news – I eventually concluded that bad news should be heard, not so we can wallow in depression and self-pity, but because hearing bad news is the first and most necessary step towards making the world a better place. As disturbing as bad news can be, it often is the impetus for positive change. Bad news may leave people frustrated, dispirited, and helpless, but when bad news inspires us to make a difference, it has the effect of bringing out the best in the human spirit, allowing us to find the solutions to the problems that plague us. To make ourselves better, we need bad news.

For example, take the Parkland school shooting in February 2018. In the aftermath, many people struggled to understand how such a thing could have happened. When I first heard about the incident, I was shocked, struggling to comprehend and grasp what had occurred. A few days later, however, I came across an article that detailed the biographies of the seventeen victims. As I scrolled down the list, tears began to stream down my face. I saw profiles that reminded me of students I knew and I also saw a profile that reminded me of myself. It described a seventeen-year-old boy named Nicholas Dworet. Nicholas was tall with blonde hair and blue eyes, like me; not only was Nicholas a swimmer, like me, but he was committed to swim at the University of Indianapolis next fall. Yet, he would never get to fulfill his dreams of attending college and pursuing the sport he loved.

Gradually, my sadness and heartbreak transformed into fiery frustration. I was tired of senseless gun violence in our schools; I was tired of hearing “thoughts and prayers” instead of demands for change. I had finally had enough.

Soon after, I heard about the March for Our Lives movement, the student-led demonstration that would take place in Washington D.C. I had never attended any sort of march before, but I knew this was a chance to use my voice along with hundreds of thousands of activists and demand change. On March 24, 2018, I woke up at 3:45 AM and made my way to our capital to march with my friend. We stood with our signs, marched on Pennsylvania Avenue with fellow students, and made our voices heard. I had never felt so empowered.

What came out of the Parkland shooting for me and many others was a newfound passion for political activism and the resolve to fight for better laws to prevent gun violence. I learned how important it is that young people stand up and fight for what we believe in. Finally, I understood that exposure to bad news is necessary because it can turn tragedy into something good, something that can inspire us to make change for the better.

Of course, no one wishes for bad news. That ACT essay perspective I mentioned made a good point: If we hear too much bad news, our hope for a brighter future may be crushed. In the face of catastrophe, we may just want to give up and stop trying. I felt that way after the Parkland shooting. However, out of our darkest fears and deepest despairs must come the resolve to make things better. To paraphrase, Edmund Burke once famously wrote that evil triumphs when good people stand by and do nothing. We have to be the force for positive social change. To become that force, we must confront the evil around us. When we learn of bad news, a school shooting, a race riot, or the murder of a journalist, we must resist the temptation to flip the channel or turn the page. As tough as it may be, we have to see the bad news as a chance to do something about it.

Recently, the US Congress banned bump stocks, which will keep someone from converting a legally purchased rifle into an automatic weapon. This will not end gun violence in America, but it is a critically important step toward making our schools, shopping malls, hospitals, and synagogues safer. That ban was passed because people were motivated by the grim reality of mass shootings in America. They accomplished this progress because they had the courage to confront a difficult truth and the conviction to act on their beliefs. We have to stare bad news in the face and work to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Only then will we build the country we want.

Mar 24, 2019 | Editorial, Opinion

By Ketaki Tavan ’19

This past Friday’s LeBow Oratorical competition reminded me of what now feels like a distant high school memory: my 5-person, trimester-long Public Speaking class that I opted to take instead of Driver’s Ed. Every time I’m asked about my favorite class I’ve taken at Pingry or course recommendations from classmates, I unfailingly circle back to Public Speaking.

I initially gravitated towards the course due to an interest in improving my speech writing and delivery skills. We worked on these skills every day through observation, discussion, and practice. Class flowed freely and in accordance with what was happening around us — if there was a major speech at Pingry or in the wider world that week, we’d make it a point to discuss what worked and what didn’t, what we’d do differently and how we’d emulate the high points.

The practical speech writing and delivery skills (like cold-reading, for example) I took away from the course should not be overlooked — they’ve stuck with me to this day, and thanks to my experience with them I’ve pushed myself to give speeches to various circles in my community several times since the course ended. But personally, what made the course so special weren’t these takeaways that I anticipated when signing up, but rather the takeaways that I truly didn’t see coming.

Because of the nature of speech writing itself and the frequency with which we did it in the class, Public Speaking became a vehicle through which I was able to really process my ideas and feelings. I came out of the course having reflected on some of my own experiences and views on the world as well as some of the most effective ways to share them. I left with a portfolio full of these reflections that will not only inspire future pieces but also serve as a unique form of a diary documenting the ideas I grappled with throughout the course.

Not only did Public Speaking allow me to learn more about myself, but it also allowed me to learn more about my classmates. Because of the vulnerable and personal nature of speech writing, when I listened to the speeches my peers brought to class each day, I learned so much about their personalities, views, and how they contributed to a truly diverse Pingry community. Speeches often sparked political, social, and academic discussions where we learned about each of our viewpoints and, in terms of speech writing, how to strengthen them rhetorically. We learned to debate thoughtfully and intelligently with each other because it was the way we were taught to craft arguments through our speeches.

My class became a mini-community of friends who came in to each meeting excited to hear what the others had to share. We learned from each other and grew closer because of what each of us shared at the podium on any given day. This was a collaborative experience through which we took inspiration and were constantly offered advice by our peers. Each of my pieces became what felt like a group-effort from several people who really cared about the final product.

While Public Speaking may not catch most students’ eyes when searching for courses, I encourage my classmates to consider the hidden treasures that the class holds. An opportunity to learn skills that will universally serve you well in the future, as well as engage with the diversity of thought and personality within yourself and your community, Public Speaking truly is worth a trimester from each and every student.